Not to be accused of “illegal gatherings,” if you hear the regime criticized at a restaurant’s table you should stand up and leave immediately.

by Kok Bayraq

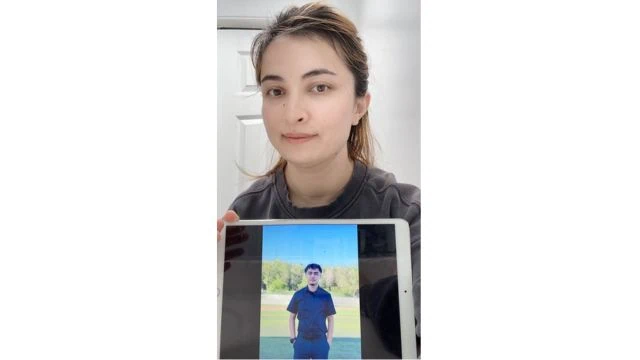

Sehibe Sayramoglu’s 24-year-old brother, Quddusjan Abduweli, was sentenced to five years and four months in prison for “disturbing public order by illegal gathering.” Sehibe lives in the USA.

According to the court, the process of “illegal” gathering is as follows: Quddusjan Abduweli and a friend come to Qumul from Bortala to look for work; their friends from Qumul meet them at a restaurant. At the table, there was a conversation about a friend who had been convicted two years before. Somebody commented that he was a good man and was just caught up in the wind of politics.

Quddusjan’s “crime” was to listen to those provocative words instead of standing up and leave at once an “illegal” meeting where a prisoner was praised as a good man and the decisions of the state authorities were implicitly criticized.

Sehibe came to know her brother’s fate from their parents’ eyes, faces, and voices on an Internet call. “When I saw them after the trial, it was as if they had aged 20 years overnight,” she said. After the court’s decision, the parents could only tell her, “Your brother will be educated again for a short time.” Because talking about more details than this would make them “neighbors” of Quddusjan in jail.

She learned about her brother’s “crime” and that his jail term was five years and four months, from Radio Free Asia. She tweeted, “My 23-year-old brother spent ten months in detention. He will spend the golden period of his life until the age of 30 in prison. Even if I would live in heaven, not America, the next six years would be hell for me. For all these years, my brother will burn in the fire, and I will burn outside.” Here, she alluded to the Uyghur proverb “Burning outside the fire is worse than burning inside.”

“I would not stop publicizing the injustice until the last day my my brother will spend in jail” she added. According to Sehibe, as soon as her brother was caught, she shared the situation with her on Twitter when she was living in Turkey. Immediately afterwards the Chinese Embassy in Istanbul called her and asked her to delete the message. Sehibe refused. Later, the Chinese national security and police contacted her. They told her that her brother’s problem was not serious, and he would be released after a short investigation or training. They asked her not to escalate the issue and to stop reporting the situation to the media. When she did not stop, they tried to silence her by using her parents. The deception and threats continued for ten months until the trial, on May 10.

Why does a superpower country trying to dominate the world spend so much effort to destroy a message on Twitter? Is this a preoccupation with some in the huge police force who may remain idle, or is it truly a concern about the internal situation of the country?

Of course, China has thousands of concerns about the Uyghurs. Today, let us talk about just one of them, “illegal gatherings.”

The gatherings of Uyghurs began to be branded as illegal in 1949, when their homeland of East Turkestan was completely colonized. At first, in the 1950s, it was considered illegal to form any political parties and institutions. During the Cultural Revolution, in the 1960s and 1970s, all religious gatherings were banned. Cultural gatherings such as Meshrep were prohibited in the 1980s and 1990s. Uyghur neighborhoods in cities like Urumqi were dismantled in the 2000s and 2010s step by step. In 2017, although not explicitly stated, family gatherings were labeled as illegal. This led to mass detentions and separation of families.

From the Quddusjan case, it appears that today’s Uyghur society is one where a gathering in which a single sentence, a single word is uttered that the government does not like, in other words, a simple gathering of friends, is also illegal.

The current level of fear of illegal gatherings is striking me. What is this lingering concern after the imprisonment of three million Uyghurs, almost the entire military capable population? Is the insecure nature of colonialism the source of anxiety? Or is it the panic of the genocidal crimes committed in the region? Or is it not fear, but a random hit of the rising, uncontrolled powerful fist? Or is it not power, but the grudge—the feeling of revenge that has been building up between the two nations for thousands of years—finding a hole to pop up? Or is this the insecurity of an unelected regime, or a manifestation of its distrust of the Uyghurs, a people they have been unable to subdue for centuries?

The answers to these questions are left to the evaluation of sociologists and historians. Here, I just want to bring some points to the attention of the human rights world. Quddusjan was just one of more than sixty people seated at the venue that day. These sixty people were arrested because Quddusjan’s sister was abroad. Although China has organized more than a thousand genocide tours to the Uyghur region, and poor and non-democratic countries have stated that they had been “persuaded” there is no genocide, China is still worried about the Uyghur situation being publicly known.

Although most of the free countries, including three permanent members of the UN security council, recognized the Uyghur situation as genocide and put a certain pressure on China, the course of the events in the region did not change or slow down. More importantly, corpses are constantly coming out of the camps: almost no one is released safely, on the contrary, the number of detainees in camps and prisons are increasing, not limited to the well-known figure of three million. The voices of many Sehibes throughout the world call to urgent action.

Source: BITTER WINTER