A young Uyghur man who risked severe punishment to take a video of himself in detention in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and his aunt, who sent the video out of the country, have both “disappeared,” according to the man’s uncle.

On Tuesday, the BBC published a nearly five-minute video showing Merdan Ghappar, a 31-year-old Uyghur model for Chinese online retailer Taobao, shackled to a bed in filthy living conditions while political slogans are played over a loudspeaker outside his barred window.

The video, and several text messages Merdan sent, appears to show some of the best evidence yet of China’s continuing policy of mass incarceration of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in a vast network of internment camps in the XUAR. This contradicts a government narrative that all detainees have “graduated” from the facilities that officials refer to as “vocational schools.” Up to 1.8 million people are believed to have been held in the camps since April 2017.

Merdan was initially held in a police jail with dozens of other detainees after being made to return from where he lived in Guangdong province’s Foshan city to his ancestral home in Kuchar (in Chinese, Kuche) city, in the XUAR’s Aksu (Akesu) prefecture, to “register” with authorities in January.

But 18 days after his detention, amid reports of an outbreak of the coronavirus in the region and with Merdan exhibiting signs of illness, he was moved to an individual cell, where restrictions were slightly looser and he was able to gain access to his phone amongst other personal items, which he used to take the video.

He sent the video to his aunt, Ayshemgul Ghappar, who then forwarded it to his Netherlands-based uncle, Abdulhakim Ghappar, in early March. Abdulhakim said he and Merdan exchanged text messages relayed by Ayshemgul over the course of several days, discussing his situation in detention before all communication suddenly ceased with his nephew and sister.

“We exchanged messages for a week … [and for the last time] around March 9 or 10, I can’t remember exactly,” he said.

“He sent me a message and then he and my sister were just gone. I’ve heard nothing from my sister since.”

Abdulhakim said that while it was unclear what happened to the pair, guards at the facility where Merdan was being held “undoubtedly took his phone away.”

“It seems clear that he got in even worse trouble after sending the video—I think this is why he disappeared,” he said.

Attempts to contact Chinese government officials to confirm the whereabouts of Merdan and Ayshemgul, as well as the reason Merdan was placed in detention, have gone unanswered.

Taobao, the online retailer that had hired Merdan as a model, no longer has any record of him on its website, while any mention of him has been scrubbed from Baidu, China’s most popular search engine.

Conditions in detention

Abdulhakim told RFA he initially posted Merdan’s video on Facebook in March but removed it as the BBC proceeded with an investigation of his nephew’s case.

The British broadcaster published it Tuesday along with texts Merdan sent detailing his experience in the police jail, which he said included being hooded and shackled on both his hands and feet, held in a 50-square-meter cell with 50-60 others, and regularly hearing screams coming from a nearby interrogation room.

In the video, taken after he was moved to solitary confinement, Merdan records himself shackled by his left wrist to a bed—the only furniture in the room—while a prerecorded message in Mandarin Chinese and Uyghur denouncing “separatism” blares from a loudspeaker outside of his window. He appears to be wearing dirty clothes and seems noticeably anxious.

Merdan also sent a photo of a communique he said he found on the floor of one of the facility’s bathrooms, calling on Uyghur children as young as 13 to “repent and surrender” to authorities for acts of “religious extremism.”

Since their last communication in March, Abdulhakim said a Han Chinese friend of his nephew’s traveled to Kuchar to find him, but authorities “went to great lengths to stop her … after they knew she’d come for Merdan.”

He said the young woman was able to enter a police station where Merdan is believed to be held but was treated rudely and told by officers that they had no responsibility to inform her about his case.

“They didn’t dispute that he was being held there, they only said that they wouldn’t tell her anything,” Abdulhakim said.

Beijing describes its three-year-old network of camps as voluntary “vocational centers,” but reporting by RFA and other media outlets shows that detainees are mostly held against their will in poor conditions, where they are forced to endure inhumane treatment and political indoctrination.

Evidence of Merdan’s detention and other reporting by RFA challenges claims made in early December by Shohrat Zakir, Xinjiang’s Uyghur governor, that people at the centers had all “graduated” and are living happy lives. Zakir made the statement a week after U.S. Congress approved the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, which allows for sanctions against Chinese officials deemed responsible for abuses in the XUAR and has since been signed into law.

Last week, the Trump administration sanctioned the quasi-military Xinjiang Production and Construction Corp (XPCC) and two of its current and former officials over rights violations in the XUAR.

The move followed similar sanctions in July against several top Chinese officials, including regional party secretary Chen Quanguo, marking the first time Washington targeted a member of China’s powerful Politburo.

Successful but not immune

Merdan’s case also shows that even Uyghurs who live their lives according to the Chinese government’s expectations of their ethnic group are not immune to persecution by authorities.

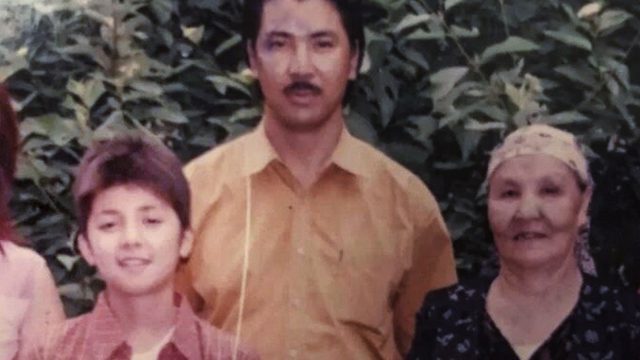

Merdan graduated from the dance program at the Xinjiang Arts Institute in Urumqi in 2007 and was invited to work for a company in Beijing before being “discovered” by an online clothing retailer, which hired him to be a model and relocated him to Guangdong’s Guangzhou city. He later began modeling for other companies as well, including Taobao, and was earning up to 10,000 yuan (U.S. $1,440) per day, according to his uncle.

However, Merdan soon found that even with his high-profile career and newfound wealth, he was still often treated as a second-class citizen by majority Han Chinese, who regularly discriminate against Uyghurs.

Merdan’s employers told him not to identify himself by his ethnic group and instead claim he had European ancestry so that nobody would question him, which he agreed to do.

“He had to make a living, after all, and it’s certainly hard to carve out a space for yourself among the nearly 1.5 billion people in China, so he went along with it,” Abdulhakim.

Merdan kept his head down and worked hard, his uncle said, noting that “he’s not really interested in religion—he’s not very interested in politics, either.”

At some point, he bought a large apartment for around 800,000 yuan (U.S. $115,000), although he was forced to register it in the name of a Han Chinese friend because he was told that, as a Uyghur, he couldn’t do so in his own name, Abdulhakim said.

But despite his success, Merdan was arrested in August 2018 and sentenced to 16 months in prison for selling marijuana, a charge which his friends have denied.

It’s unclear whether Merdan was guilty of the charges against him, but reports suggest that Uyghurs are more likely to face conviction in China’s judicial system than Han Chinese, and those who have served prison sentences are also seemingly at higher risk of later detention in the camp system.

Upon his release from prison in November, Merdan tried to resume work, but two months later “some Uyghur police officers [from Xinjiang] showed up along with local police” who “said they were taking him back” to the region, where he was detained on his return.

“Ultimately, I see the fact that he’s Uyghur as the primary reason for his detention,” Abdulhakim told RFA.

“When he went to Guangzhou, his agent told him not to openly advertise that he was Uyghur in his business dealings,” he added.

“People in China think like this: if you’re Uyghur or from Xinjiang, it doesn’t matter how talented you are, you can’t be successful. So those were the grounds for his modeling career.”

Reported by Nur Iman for RFA’s Uyghur Service. Translated by Elise Anderson. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.

Source: Copyright © 1998-2016, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org.