A book by Timothy Grose examines Beijing’s project of taking Uyghur students to boarding schools far away from Xinjiang to “sinicize” them.

by Massimo Introvigne

“Ethnic engineering” has long been one of the CCP’s grand projects. Non-Han should be “sinicized” and led to accept their status as members of “ethnic minorities” (minzu), looking at the Han as “elder brothers” and models, and enacting the role the CCP has devised for them. The Uyghurs in Xinjiang have resisted both the imposition of the Chinese language and the eradication of their Islamic religious practices. The CCP has increased the repression by throwing millions of Uyghurs into the dreaded transformation through education camps, but its long-term hopes are placed in “sinicizing” the next Uyghur generation through education.

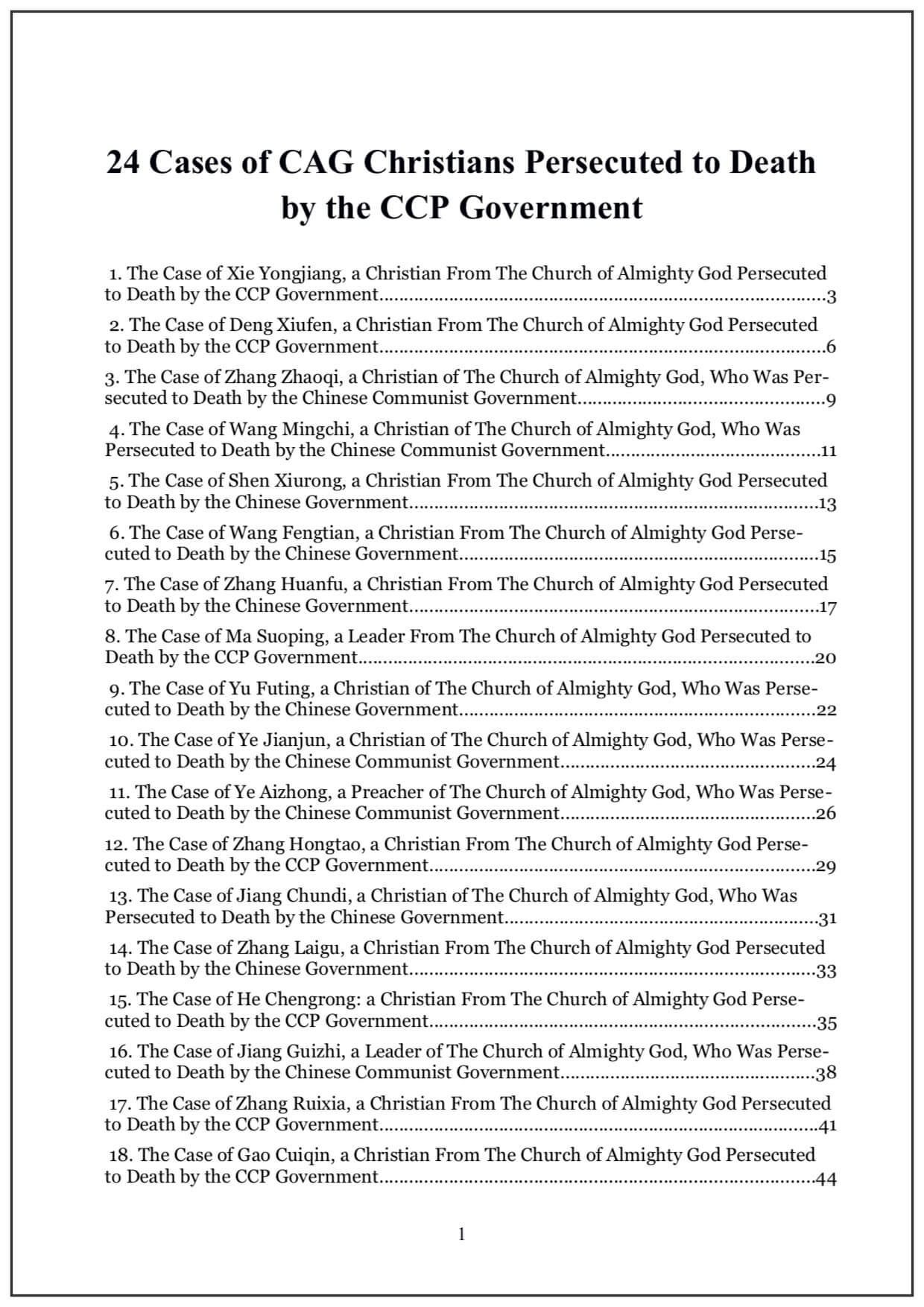

Timothy A. Grose, a professor of China Studies at Rose-Human Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana, has published Negotiating Inseparability in China: The Xinjiang Class and the Dynamics of Uyghur Identity with Hong Kong University Press (2019). It tells the story of the Xinjiang Class, modeled on the Tibet Class, which takes annually some 1,600 Tibetans to boarding junior high schools, and another 3,000 to boarding senior high schools, far away from Tibet, nearly 20% of all Tibetan high school students.

In 1999, a similar program was announced for Uyghur students and regarded as a matter of “national security.” In 2000, the CCP drafted two key documents about the project, the Ministry of Education’s “Summary of the Xinjiang Class Work Meeting” and the “Administrative Procedures of the Xinjiang Class.” They clearly spell out the aim of the Xinjiang Class: create a group of young Uyghurs who “support the Chinese Communist Party’s leaders, love China, love socialism, defend the unity of China.” The classes should “strengthen their support for the CCP” by teaching the works of Karl Marx and the CCP leaders. As Grose notes, “the CCP’s intentions were clear from the beginning: the boarding schools were established to be insulated spaces for promoting party ideals. CCP officials and school administrators give primacy to political indoctrination before educational goals.”

The Xinjiang Class is advertised through a state-of-the-art publicity campaign, emphasizing that tuition fees are largely covered by the CCP and that the boarding school alumni are better positioned in the job market than those educated in Xinjiang. The program has more applicants than places available, and in 2015 the CCP fixed a cap of 9,880 enrollments per year.

The students are transported to coastal cities as far away from Xinjiang as possible and permitted to return home only once a year; visits by parents are discouraged. Courses are taught in Chinese only. There is a point system rewarding and punishing students, and points are deducted for speaking Uyghur outside of some limited “designated times” when this is allowed. Students receive “sinicized” names and are immediately told that any religious activity is forbidden, including private prayer. If one student is caught praying in his or her room, the entire dorm is punished. The only concession is the offer of halal cafeterias, although Grose claims that non-halal food is sometimes surreptitiously introduced there.

Uyghur students should celebrate Chinese feasts rather than Muslim feasts. For example, to celebrate the Qing Ming Festival, which is not part of the Uyghur tradition, students should visit the “Martyr Parks” and tidy the graves of CCP civil war victims. By doing so, Grose notes, “students learn that the ‘New China’ would not exist without the Communist Party. Second, as the students sweep away rubbish that has collected around the tombs, the motion becomes symbolic of ‘sweeping away [their own] backwardness.’”

The aim of the CCP is to “convert” elite Uyghur students who will become loyal supporters of the party, come back to Xinjiang, and help “sinicize” the region. There is only one problem with the project. It does not work. Grose does not claim that all students are unhappy with the Xinjiang Class. Some appreciate the education and the opportunities, and go back to Xinjiang where they work as bureaucrats or police officers. They are, however, a minority. Most students interviewed by Grose describe the boarding schools as “being like jails.” As a reaction, they reinforce their ethnic and religious identity.

Everywhere in the world, young men and women like what is forbidden. Some young girls started veiling after attending the Xinjiang Class. Others rediscovered prayer, or in Beijing went to the Saudi Embassy to get copies of the Quran not annotated by the CCP. Few befriended Han Chinese students, but many made friends (and some married) Muslim students from other countries (while they generally disliked the Hui, who are Chinese-speaking Muslims). A telltale sign of all this was that, when Turkey defeated China in the 2002 soccer World Cup, the Xinjiang Class Uyghur students rooted for Turkey and celebrated.

And many Xinjiang Class graduates tend not to return to Xinjiang. They stay where they attended high school and go to university if they can. Nearly 50% will never return home. They use the opportunities offered to residents of other provinces to obtain passports more easily than Uyghurs in Xinjiang and go abroad: Turkey, Europe, Australia, United States, where they “often became indefatigable advocates of Uyghur human rights.” Significantly, they mention lack of religious liberty as one main reason not to go back to Xinjiang.

In 2015, the CCP media broadcast interviews with one Tursun, a 23-year old Uyghur man who allegedly went to Afghanistan to train as a terrorist. Arrested upon his return to China, he was now repentant and praised the CCP. The interesting fact is that Tursun was a graduate of the Xinjiang Class. While his confession from jail was intended as propaganda, it also unintentionally disclosed to the audience how the Xinjiang Class project may spectacularly fail.

Source: Bitter Winter