Known as a womanizer and a billionaire, but also as a strong supporter of the CCP, Shi Yongxin’s wrongdoings eventually became too infamous to overlook.

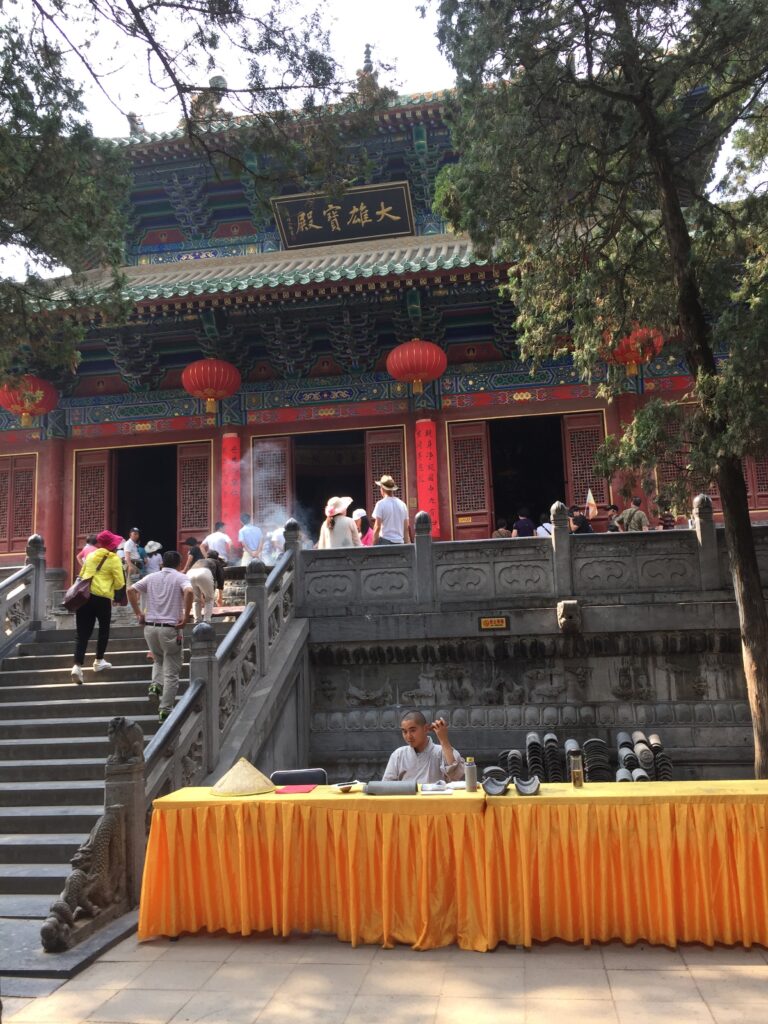

The arrest on July 25 and the defrocking of Shi Yongxin, the former influential abbot of China’s famous Shaolin Monastery, have caused shockwaves across the country’s religious scene. Known as the birthplace of Shaolin kung fu, the monastery now faces a scandal that could undermine the credibility of China’s state-sanctioned Buddhist organizations.

Shi Yongxin, originally named Liu Yingcheng and born in 1965, became the abbot of Shaolin Temple in 1999. During his tenure, he turned the once dilapidated monastery into a worldwide brand. Known as the “CEO monk,” he promoted Shaolin culture aggressively, licensing its name in over eighty countries for products ranging from bottled water to video games.

Beneath the glossy image of kung fu shows and global business dealings, Shi’s leadership has been clouded by longstanding misconduct allegations. In 2015, a whistleblower claimed he kept mistresses and owned expensive cars. While a provincial investigation cleared him of any wrongdoing at that time, the accusations continued to linger.

A decade on, the government-controlled China Buddhist Association has confirmed that Shi is under criminal investigation for embezzling temple funds and assets, maintaining improper relationships with several women, and fathering illegitimate children. These revelations have resulted in his defrocking and the annulment of his ordination certificate, effectively removing his monastic status.

The scandal was made public on July 27, 2025, when the Shaolin Temple’s management issued an official statement detailing the allegations. Shortly afterward, the China Buddhist Association issued a statement supporting the investigation and criticizing Shi’s actions as “severely damaging to the reputation of Buddhism and the image of monks.”

The association emphasized that “no one is above the law or the moral principles of their faith,” making a rare and decisive move to distance itself from one of its prominent leaders. The Henan Provincial Buddhist Association also officially requested the revocation of Shi’s monastic credentials, which was approved in accordance with China Buddhist Association regulations.

Shi’s downfall quickly resulted in the disbanding of his business activities. Public records show he was connected to eight companies, with five having their licenses revoked or canceled. These include subsidiaries in kung fu academies, traditional medicine, and intangible asset management.

The Zhengzhou Buddhist Association, Henan Provincial Buddhist Association, and China Songshan Shaolin Temple are all currently under audit. Additionally, authorities are investigating 17 more companies linked to Shi, heightening concerns about widespread financial mismanagement and the possible use of religious influence for personal benefit.

The scandal has ignited fierce discussions on Chinese social media. Numerous users condemn Shi as a “fallen monk” who misused his position for personal gain, including wealth and influence. Conversely, some believe his actions expose the risks of “political Buddhism,” where monks linked to the government prioritize commerce and political ties over spiritual duties.

This crisis goes beyond individual misconduct, exposing the flaws in China’s government-run religious institutions. These bodies, overseen by state-approved associations, are tasked with enforcing doctrinal discipline and ensuring ideological alignment with the Communist Party, often compromising spiritual independence.

Shi’s case demonstrates how this model can be exploited. As both a religious leader and a business tycoon, he blurred the lines between faith and commerce. Serving as a deputy to the National People’s Congress from 1998 to 2018 strengthened his political influence, enabling him to expand a large empire with minimal oversight.

China’s religious policy is founded on the principle that “religion serves socialism.” All religious groups are required to register with state-approved organizations responsible for overseeing doctrine, personnel, and finances. For instance, the China Buddhist Association oversees monk vetting, approves ordinations, and monitors conformity to Party directives.

Although this system aims to prevent political dissent and foreign influence, it also opens doors for corruption. Monks such as Shi, who benefit from political favor and economic success, can act with impunity until public pressure or internal conflicts force accountability.

The Shaolin Temple serves as both a religious site and a cultural symbol. Founded over 1,500 years ago in Henan province, it is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site and is famous worldwide for its martial arts legacy. The Chinese government has carefully shaped its image as a symbol of national pride and soft power.

Shi’s commercialization of the temple was initially seen as a success in promoting cultural diplomacy. He played a role in founding Shaolin-themed hotels, kung fu schools, and organizing international tours. However, critics argue that this shift turned the temple into a tourist destination instead of maintaining its spiritual sanctuary.

Shi Yongxin’s removal from his position signifies a pivotal moment. His ascent and subsequent fall highlight the ongoing tension between faith and politics. Additionally, they underscore the difficulties China encounters in regulating religion—balancing the desire to oversee beliefs while encouraging cultural heritage.

Whether this scandal results in a crisis within the China Buddhist Association remains uncertain. But one thing is certain: the arrest of the “CEO monk” has shaken the core of China’s Buddhist establishment, prompting a confrontation with the values it professes to uphold.

Source: Bitter Winter