Oxford University Press publishes Massimo Introvigne’s survey of the most persecuted religious movement in China

by Ruth Ingram

Viciously persecuted, tortured and slandered by a catalogue of spurious news headlines, members of The Church of Almighty God (CAG) have been hunted by the Chinese government with a vengeance that verges on vendetta. Through the fake news, the CCP was able to tarnish the CAG’s image at home and abroad, although in recent years scholars have proposed a different version of the facts, which is slowly being accepted by democratic governments and media.

In an attempt to understand the movement itself and the rationale behind the CCP’s relentless hounding of its faithful, Professor Massimo Introvigne, founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), and editor-in-chief of Bitter Winter, has interviewed scores of CAG members and scoured primary news sources and Chinese government documents, both public and secret. He has interviewed officers of the Chinese police and CCP representatives, spoken to anti-cult activists and researchers who themselves are engaged in the CCP’s official campaign against the church, in his determination to separate fact from fiction in the life of this idiosyncratic new Christian movement.

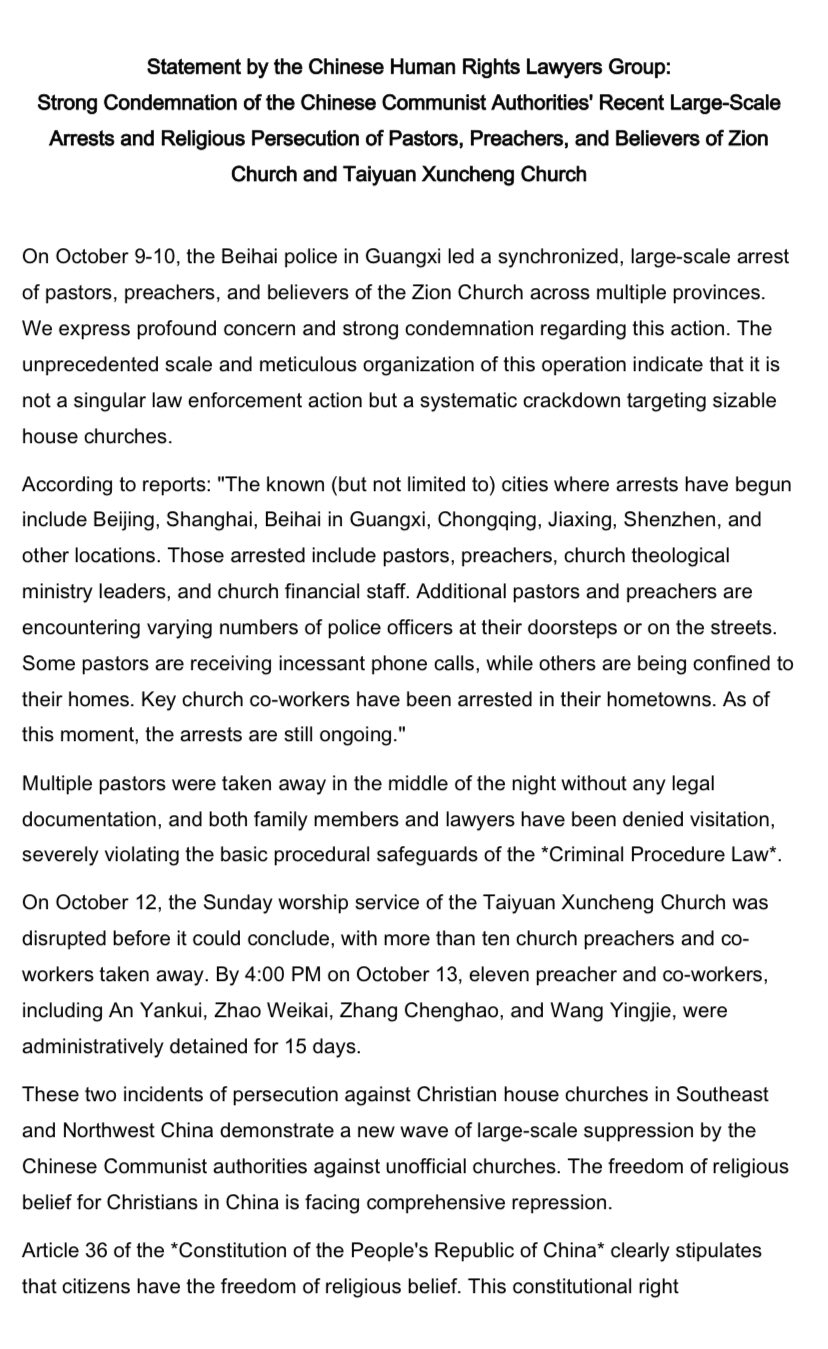

His groundbreaking conclusions can be found in a new book, “Inside The Church of Almighty God: The Most Persecuted Religious Movement in China” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), which sets out to examine its basic tenets, answer some of the questions and controversies that surround it, and to make public a campaign of relentless untruths perpetrated by the CCP, in their determination to discredit and destroy the CAG.

Tracing the earliest days of the group, which emerged during the early 1990s revival of Chinese Christianity, and which was initially called “Eastern Lightning,” Introvigne takes the reader on a tour of the movement itself against the backdrop of the Chinese government’s obsession with, and determination to rid the country of, what it calls xie jiao, or heterodox teachings. He chronicles the milestones of the church until the present day, with Xi Jinping’s all out push to eradicate it altogether and “sinicize” everything that lives and breathes in his President for life’s “New Era.”

Although the usual English translation of xie jiao is “cult” or “evil cult,” which would immediately resonate with a Western audience as something undesirable, Introvigne explains that the historical meaning of the word has its roots in the late Ming era, when governments were preoccupied with a fear of being taken over. And herein lies the problem to this day with any group that refuses to come under the over-arching canopy of CCP rule: it is perceived as a threat and must be destroyed. Some religions have been tolerated and survived in a State-supervised form until now, but in the face of Xi Jinping’s concerted drive to bring all religions under the Party banner, even their future hangs by a thread.

With Government estimates of CAG followers now numbering around four million, CCP officials interviewed for this book have dubbed it the “New Falun Gong,” and report more police officers deployed hunting its members these days than those of Falun Gong. Of course, CAG’s theology is totally different from Falun Gong, and the label reflects its perception by the CCP rather than any inherent characteristic of the movement.

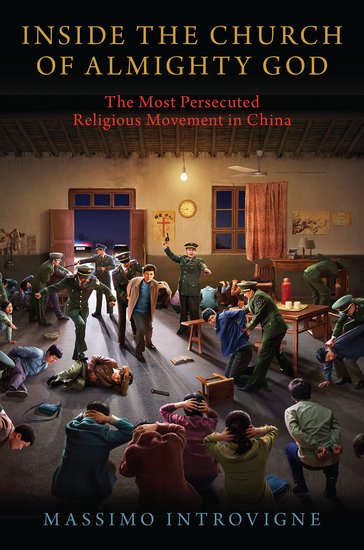

Introvigne is a sociologist, and the book itself is a scholarly work, although at times reads like a fast-moving thriller, with tales of kidnappings, intrigues, a gruesome murder, a grizzly child maiming, and a nail-biting airport escape. That this account is not simply about a movement, but human lives destroyed or cut short, is vividly illustrated in the first few pages of the book with Introvigne’s graphic descriptions of gratuitous violence meted out to some of its adherents, who for reasons of conscience refused to give up their faith or betray fellow worshippers. We read the rest of the book with the last moments of these nine witnesses to CCP brutality etched on our minds.

Although some scholars claim that CAG beliefs fall broadly within those of Protestantism, the roads diverge markedly with their belief that Jesus has been incarnated as a Chinese woman, worshiped as Almighty God, who it is claimed has ushered in a new era for the world. The movement would not disclose her name, but some scholars believe she is called Yang Xiangbin, born in north western China in 1973. Whereas the Old Testament is termed the Age of Law, and the New Testament and the era inaugurated by Jesus, the Age of Grace, they believe the incarnation of Almighty God has ushered in the latter days and the “Age of the Kingdom.”

People felt that Almighty God’s words helped to unlock mysteries in the Bible and showed them how they should live. Through the subsequent one million words that Almighty God uttered between 1991 and 1992, the followers became persuaded that “while Jesus had performed the work of redemption, only the new revelation of Almighty God could eradicate human corruption,” and that the person who was speaking through the messages was in fact the incarnation of Almighty God.

After a period of consolidation, the movement exploded from 1995 onwards, initially trawling in thousands from the existing underground churches, with one million having joined the ranks by 2005. Although the underground churches in their many forms were consistently persecuted in the nineties, and the CAG was repressed since its very beginnings, and a special police task force was later set up to hit them hard. Zhao and the person CAG members worship as Almighty God fled the country and were granted asylum in the United States. The movement has since been directed from abroad.

The CCP pulled out all the stops to eradicate the Church, confiscating funds, hounding leaders, brutally and sadistically torturing most of those who were arrested, some to death. Some 400,000 were arrested before the end of 2019, with 146 cases of death at CCP hands since the Church’s foundation.

A favored tactic to discredit the movement in the eyes of those at home but also the world, has been a relentless stream of ghoulish attacks, well publicized to have been carried out by the CAG, but subsequently proven to be unrelated. The mud sticks however, and when in 2014 five people entered a McDonald’s restaurant in Shandong claiming to represent “Almighty God,” and bludgeoned an innocent customer to death for not giving her telephone number to one of the assailants, the CCP claimed that CAG was responsible. When the trial of the assassins proved that they belonged to a different group, also regarding its two female leaders as “Almighty God” but unrelated to the CAG, most international media had already repeated the CCP version that the CAG was guilty, and did not correct it. Other atrocities which it has suited the CCP to lay at the feet of the CAG, but on closer examination the evidence found to be fatally flawed, still reverberate in the corridors of so-called “evidence” to discredit the movement. Introvigne’s investigations found that on occasions some traditional church bodies, upset by the loss of their own members to this group, were content to collaborate with the CCP in blackening CAG’s name.

Angelia Zheng, a former teacher in China, is one of some 1,000 CAG asylum seekers in South Korea. Her refugee application was rejected by the Korean government, and she lost her appeal with the third-level court of South Korea. She has now submitted a new application, and lives in a twilight world of uncertainty as to where her future lies.

After becoming a CAG member in October 2007, she was forced into a life on the run in February 2008, fleeing from one city and one province to another, before finally escaping to South Korea in November 2014. She has not seen her family for twelve years. She feels that many governments around the world have been sucked into the fake news campaign of a regime that has resorted to underhand tactics to blacken the name of a group that they cannot destroy in any other way. “Some government authorities buy such fake news, resulting in the denial of CAG asylum seekers’ applications,” she said. “There are even decisions to deport them to China.”

According to a stark table towards the end of Introvigne’s book, thousands of CAG refugees are worryingly in limbo, their lives in the hands of democratic Governments, many of which have even gone as far as to reject applications and issue departure orders which if carried out, will almost certainly result in prison, if not worse.

Angelia has read Introvigne’s book and she hopes that, although obviously the work of an outsider, it will shed a new light on the CAG movement. “CAG members are a group of friendly and peaceful Christians who want nothing more than to practice their religion freely,” she pleads.

Source: Bitter Winter