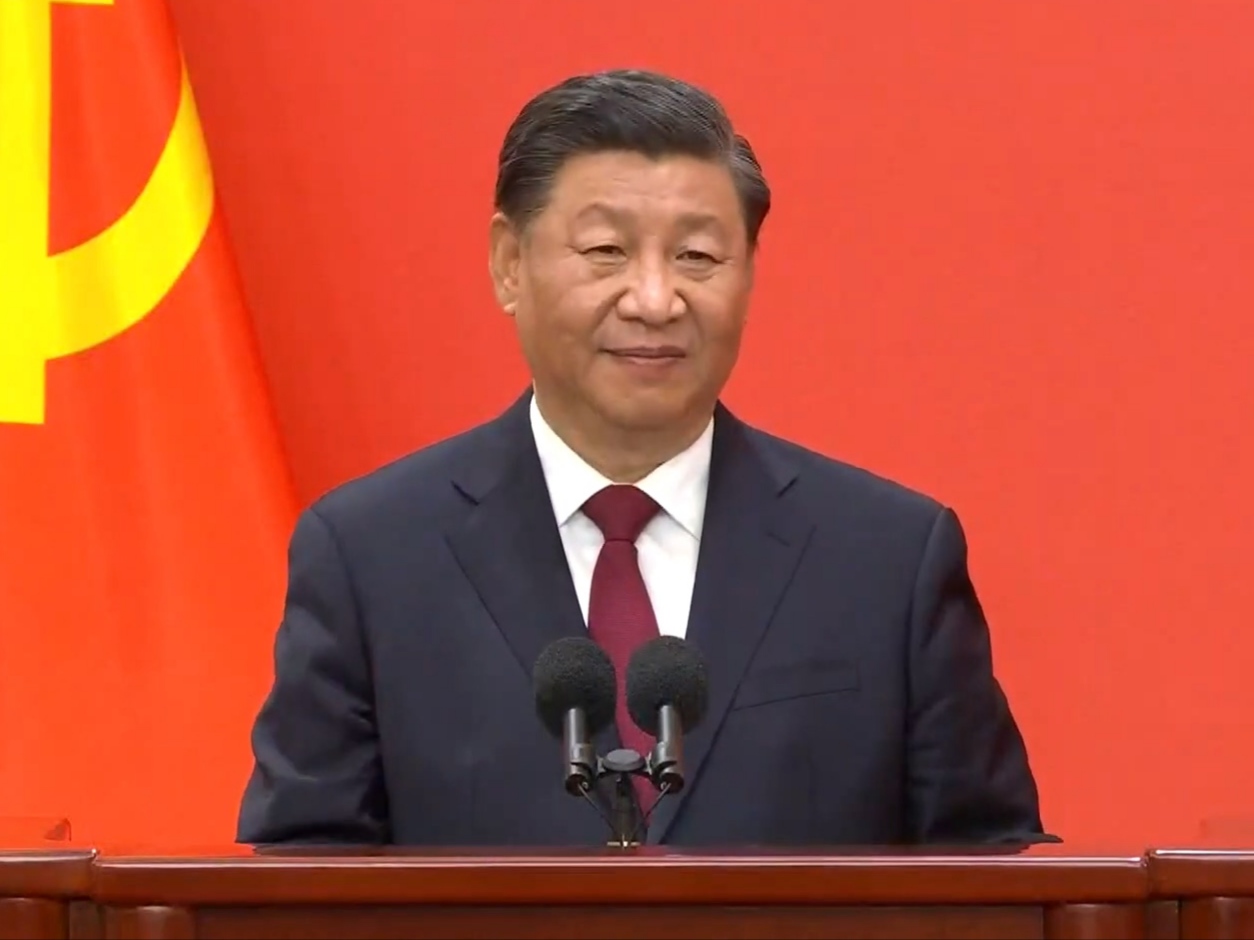

Meeting for the first time in six years this week in Busan, South Korea, President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping conducted a closely watched meeting on a wide range of topics such as trade, tariffs, rare earths, and fentanyl.

In the weeks leading up to the Thursday meeting, activists and a bipartisan group of U.S. lawmakers had been pressing to place human rights concerns prominently on the agenda. In the context of recent arrests of religious leaders, religious freedom was one of the primary areas of concern.

Human rights monitors and religious freedom groups have documented a marked intensification of pressure on unregistered house churches, underground congregations, and other faith communities across China in recent months.

One of the most prominent recent incidents involved the detention of Pastor Jin Mingri, leader of the large Zion Church movement. His family reports that he was arrested alongside other church leaders in a massive security operation described by advocacy groups as part of the most extensive campaign against independent Christians in decades.

The arrests, which sources say were justified by Beijing on charges related to online dissemination of religious content, have been seized upon by U.S.-based groups and family members as emblematic of a broader effort to force religious groups into state-controlled structures.

The case of Jimmy Lai — the Hong Kong media entrepreneur and Catholic convert who founded the now-defunct pro-democracy paper Apple Daily — has also figured prominently in entreaties from U.S. officials and civil-society actors.

Lai has been detained and prosecuted under national security laws in Hong Kong since 2020. A bipartisan cohort of U.S. senators and other political figures has repeatedly urged his release and spotlighted reports alleging that his treatment in custody has interfered with his ability to practice his faith. Those calls intensified in the run-up to the Busan meeting, with letters and public appeals urging the U.S. president to raise Lai’s situation directly with Xi.

One reporter asked Trump, as he was boarding Marine One for the trip, whether he would raise the Lai case. Trump responded, “It’s on my list — I’m going to ask,” adding that Lai and Xi “are big enemies, so we’ll see what happens.”

In the days leading to the summit, human rights organizations and some lawmakers — including a group of senators who publicly petitioned the White House — mounted a visible campaign to ensure that religious liberty and individual cases were discussed, arguing that economic or security gains should not come at the expense of human rights advocacy.

Public reporting on the Busan meeting’s content has emphasized deals on trade and cooperation on issues such as fentanyl and rare-earth exports. Major outlets’ live coverage and official summaries so far focus on those outcomes and do not report a clear, confirmed discussion of Zion Church leaders or Jimmy Lai during the leaders’ private talks.

Readouts of bilateral conversations are often incomplete in the immediate aftermath of summit diplomacy, leaving open the possibility that human-rights grievances were raised discreetly or will be addressed in follow-up channels. For now, however, there is no public indication that the high-profile religious-freedom cases central to advocacy campaigns were brought up in the leaders’ public statements.

Source: ICC