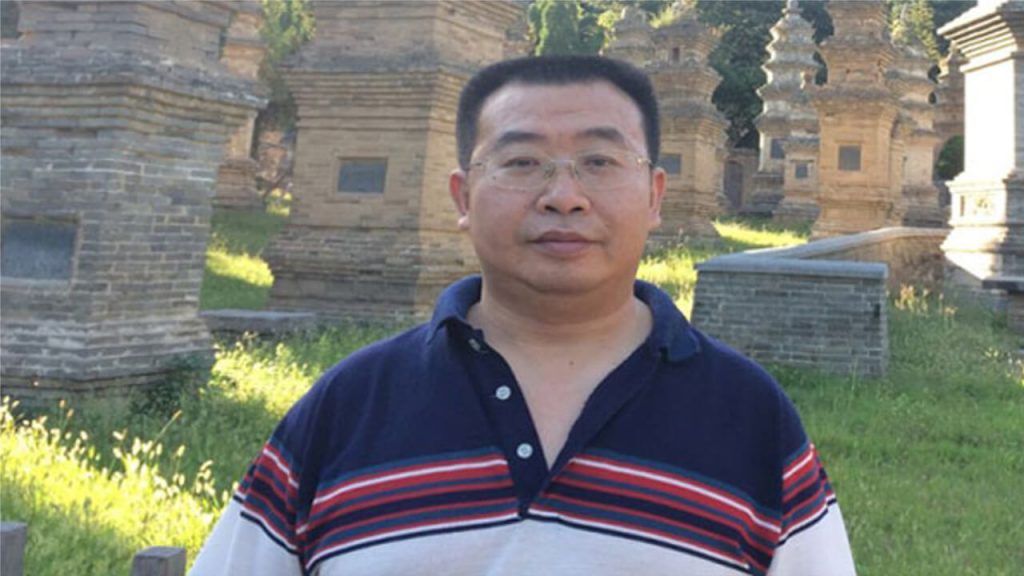

The wife of a jailed Chinese rights lawyer caught up in the July 2015 crackdown says he is suffering from memory loss in prison, raising concerns that the authorities may be dosing him with psychoactive medications.

Jiang Tianyong was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment on charges of “incitement to subvert state power” last November, after he pleaded guilty at what his family said was a show trial in August.

Photo courtesy of Jin Bianling.

Jiang has yet to be transferred to prison from the Changsha No. 1 Detention Center, where he was held under pretrial detention and pending appeal, but was recently permitted a visit from his sister, who found his health deteriorating and his memory unreliable, his U.S.-based wife Jin Bianling told RFA.

Jin said Jiang’s memory has shown “serious deterioration” since the last visit by a lawyer or family member, leading the family to suspect he has been force-fed with psychiatric medications — a method the Soviet Union used against political prisoners that China has also employed.

She said fellow rights lawyers detained in a nationwide police operation that began in July 2015 have reported being force-fed various types of medication.

“All of the lawyers detained in the July 2015 crackdown have been force-fed medication,” Jin said. “That’s why I suspect that Jiang Tianyong has too.”

“I call on the detention center authorities to allow Jiang Tianyong to have a proper health check-up and treatment, and not to use dubious medication on him,” Jin said.

Fellow human rights lawyer Ma Lianshun said many of the lawyers detained in the crackdown have suffered lasting effects from the medication they were forced to take while incarcerated.

“This has really affected their brains and their mental functioning,” Ma said. “Those kinds of medications definitely cause memory function to deteriorate.”

Jiang, 46, was detained in Changsha after he went there to visit the family of jailed human rights lawyer Xie Yang, who had filed a complaint that he was tortured during his spell in detention.

Stability maintenance regime

Rights lawyer Xie Yanyi, who was himself detained during the crackdown, said Jiang had been trying to help to “rescue” Xie from detention at that time.

“Back then [in July 2015], the stability maintenance regime was doing everything it could to try to get the families of the lawyers to cooperate, for the sake of stability,” Xie said. “Now, the whole situation seems to have escalated, and I think they may be even more unscrupulous when it comes to Jiang Tianyong.”

Beijing-based activist Hu Jia said the crackdown on the legal profession is still under way.

“Jiang Tianyong was detained and sentenced in Changsha, and then we have Wu Gan, who may not be a lawyer, but who was detained as part of the July 2015 crackdown,” Hu said. “He got a very harsh sentence of eight years, the heaviest sentence of the crackdown.”

“The Chinese government is continuing to persecute human rights lawyers, more and more harshly,” he said.

Jiang’s sentence was based on his setting up of a campaign group in support of rights lawyers detained in a nationwide police operation targeting the profession since July 2015, the prosecution said during his trial.

Jiang had “speculated” on politically sensitive cases and “incited others to illegally gather in public places” and “stirred up” public opinion, the indictment said.

He had also “seriously harmed state security and social stability” by “attacking and slandering the current political system, and attempting to overthrow the socialist system,” it found.

London-based rights group Amnesty International said in its 2017 annual report last week that the administration of President Xi Jinping has pursued a “ruthless campaign of arbitrary arrests, detention, imprisonment and torture and other ill-treatment of human rights lawyers and activists.”

It said the authorities are continuing with the widespread use of “residential surveillance in a designated location.”

“[This is] a form of secret incommunicado detention that allowed the police to hold individuals for up to six months outside the formal detention system, without access to legal counsel of their choice, their families or others, and placed suspects at risk of torture and other ill-treatment,” the report said.

It has been used to curb the activities of human rights defenders, including lawyers, activists and religious practitioners, the group said.

Source: Copyright © 1998-2016, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org.