Inaugurated on July 19, the dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River will have a devastating ecological impact on Tibet and allow China to manipulate water flows against India.

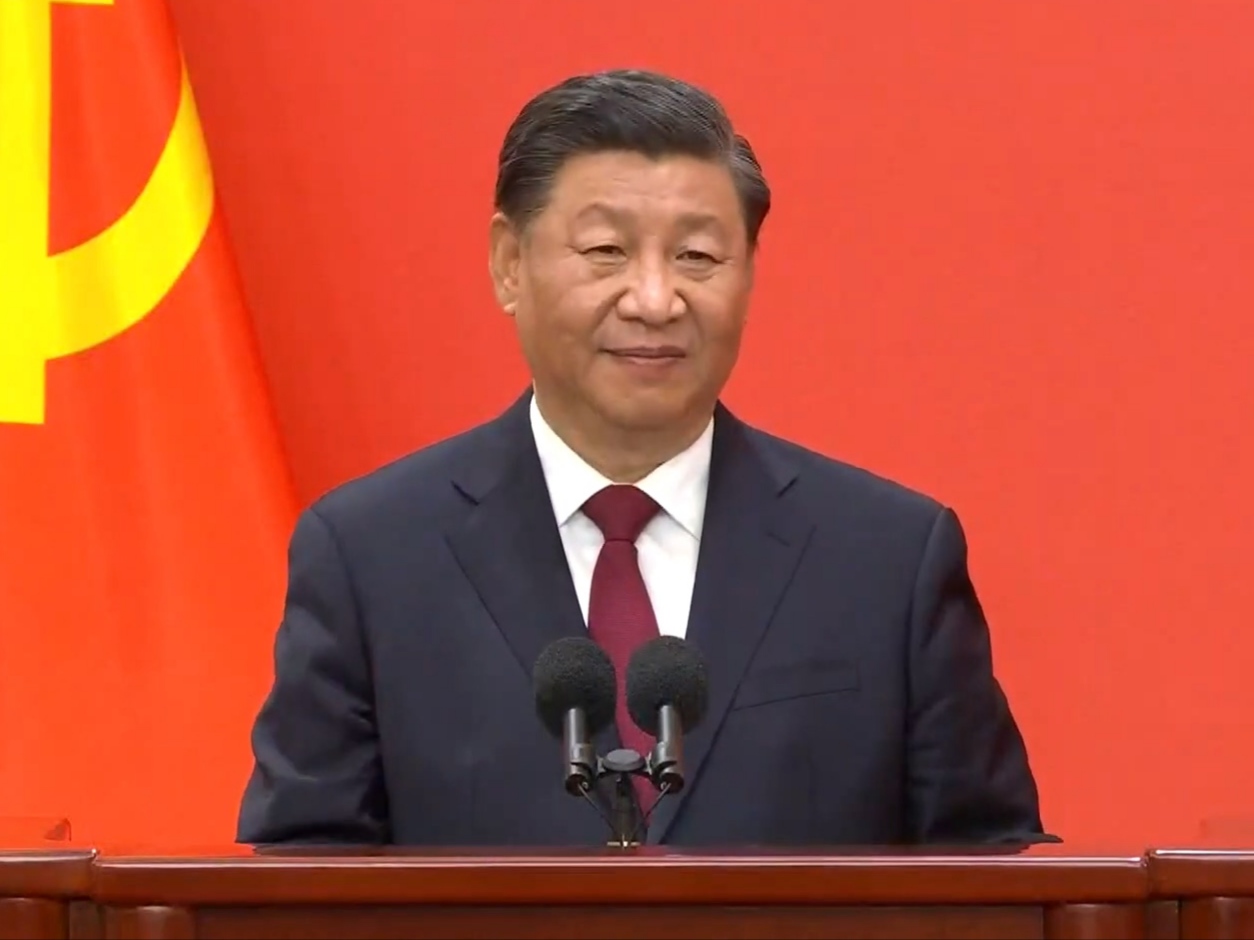

On July 19, 2025, China officially inaugurated the construction of the world’s largest hydropower dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo River in southeastern Tibet. Known as the Brahmaputra once it enters India, this transboundary river is vital to northeastern India and Bangladesh’s ecological and economic stability. The $167.8 billion project, announced by Chinese Premier Li Qiang at a groundbreaking ceremony in Nyingchi near the Indian border, has triggered alarm in New Delhi over its strategic, environmental, and geopolitical ramifications. Because of its ecological implications, it does not please the Tibetans either.

The dam will consist of five cascade hydropower stations and is expected to generate over 300 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually—three times the output of China’s Three Gorges Dam. The project is part of China’s broader “big dam” policy and is being framed domestically as the “project of the century.” However, its location—just 30 kilometers from Arunachal Pradesh, an Indian region China claims as “South Tibet”—adds a layer of strategic sensitivity.

India’s apprehensions stem from the dam’s proximity to its border and the absence of a binding water-sharing treaty with China. The Brahmaputra is a lifeline for millions in India’s northeastern states, supporting agriculture, fisheries, and daily water needs. Indian officials fear that the dam could allow China to manipulate water flows by withholding water during dry seasons or releasing excess volumes during monsoons, potentially causing artificial floods.

Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu has described the dam as a “ticking water bomb,” warning that sudden releases could devastate the Siang belt and threaten the livelihoods of local tribes such as the Adi.

The Indian Ministry of External Affairs has repeatedly raised concerns with Beijing, urging it to ensure that downstream interests are not harmed. Talks between Indian and Chinese officials have included calls for the resumption of hydrological data sharing, which China suspended in 2022 following the expiration of previous agreements.

Beyond strategic anxieties, the dam poses significant ecological threats to Tibet. The Yarlung Tsangpo River carves through one of the world’s deepest canyons and supports a rich biodiversity unique to the Tibetan Plateau. Environmental and human rights groups, including the International Campaign for Tibet, warn that the project could cause irreversible damage to fragile ecosystems.

Key ecological concerns include:

Disruption of sediment flow: The dam may trap nutrient-rich sediments, reducing soil fertility downstream and impacting agriculture as far as Assam and Bangladesh.

Biodiversity loss: The region hosts endemic species and ancient forests. Construction and altered water regimes could threaten habitats and lead to extinctions.

Seismic vulnerability: The dam is located in a tectonically active zone. Large-scale infrastructure in such areas increases the risk of earthquakes and landslides.

Water quality and temperature shifts: Changes in flow dynamics could affect aquatic life and disrupt traditional fishing practices.

China has pledged to prioritize ecological conservation and claims the project will not negatively impact downstream regions. However, skepticism remains high, especially given the lack of transparency and independent environmental assessments.

In response, India is accelerating its own hydropower initiatives, notably the Siang Upper Multipurpose Project in Arunachal Pradesh. This project is intended to assert India’s water rights and serve as a strategic buffer against potential Chinese manipulation. Additionally, India continues to advocate for the revival of the Expert Level Mechanism (ELM), a bilateral platform established in 2006 to discuss transboundary river issues.

India’s broader diplomatic strategy includes pressing for greater transparency, data sharing, and adherence to international norms governing shared water resources. However, China is not a signatory to the UN Watercourses Convention, limiting the scope for legal recourse.

The inauguration of China’s mega-dam on the Yarlung Tsangpo marks a pivotal moment in the geopolitics of South Asia’s water resources. For India, the project is not merely an engineering feat but a potential instrument of strategic leverage. Coupled with ecological risks deeply felt by Tibetans and the absence of cooperative frameworks, the dam underscores the urgent need for a concerted international action against China’s policy of weaponizing water.

Source: Bitter Winter