A detailed study reveals that hundreds of newspapers regularly copy and paste materials prepared by the CCP’s Publicity Department.

In contrast to other countries where media serve as critical voices countering government communication, journalism in China exists solely to disseminate official propaganda.

These are the results of the study “The Decade-Long Growth of Government-Authored News Media in China under Xi Jinping” by Hannah Waight, Yin Yuan, Margaret E. Roberts, and Brandon M. Stewart, published in the Proceedings of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and discussed on June 17 in one of the “China Briefs” of the Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions.

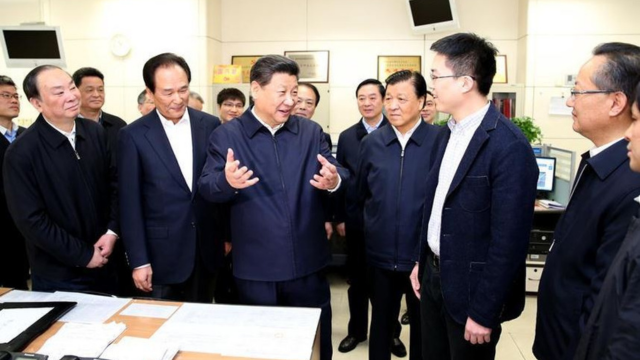

This significant study explores the systematic growth of government-produced content—referred to as “scripted propaganda”—in Chinese newspapers from 2012 to 2022, during Xi Jinping’s rise to power. The authors use a dataset containing over 11 million articles from 700 party and commercial newspapers to demonstrate how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has increasingly integrated centrally scripted content into the nation’s media landscape. Their results challenge naive notions of media pluralism in China and introduce a novel empirical framework for detecting covert propaganda in authoritarian settings.

The authors define scripted propaganda as articles from central government sources—usually the Publicity Department of the CCP (also known as the Propaganda Department) or state-run agencies such as Xinhua—distributed to various newspapers with little or no alteration. Unlike Western syndication, these articles are required to be published and frequently appear simultaneously in multiple outlets.

To detect scripted content, the researchers created a new computational method that finds clusters of similar articles published on the same day in various newspapers. This technique was validated with over 1,000 leaked propaganda directives from “China Digital Times,” confirming that the state mandated the recognized articles.

In China, scripted propaganda is almost a daily occurrence in the media. Between 2012 and 2022, party newspapers featured at least one scripted article on 90% of days. Scripted articles could comprise up to 30% of all content in major newspapers during politically sensitive times, like anniversaries, leadership changes, or crises.

The use of scripted content has increased markedly. In 2012, only about 5–7% of front-page articles in party newspapers were scripted. By 2022, this number had increased fourfold to around 20%. This rise highlights a broader trend of media centralization and ideological constriction under Xi Jinping.

Over the years, newspapers have shown less inclination to adapt or localize scripted articles. Earlier in the decade, several outlets would change headlines or add local context. However, by the end of the study period, most scripted articles were reproduced verbatim, reflecting a decrease in editorial independence and a rise in consistency within state messaging.

Contrary to the belief that propaganda is limited to party-controlled media, this study reveals that scripted content is also prevalent in commercial newspapers. Although party publications are the main channels, commercial newspapers—particularly those with substantial readerships—often feature government-written articles, frequently without proper disclosure.

Scripted propaganda extends beyond just ideological or political subjects. Although themes such as nationalism, Party accomplishments, and Xi Jinping Thought are common, the research shows that scripted content also includes topics like public health, natural disasters, crime, and lifestyle issues. This variety allows the state to shape public discourse on various daily matters.

The authors analyze the COVID-19 pandemic to demonstrate the use of scripted propaganda in crisis management. At the onset of the outbreak, the government postponed sharing crucial information while inundating newspapers with scripted narratives that highlighted state authority and minimized uncertainty. This approach limited independent journalism and influenced the public’s understanding of the crisis.

The research presents strong evidence indicating that media control in China has increased significantly under Xi Jinping. The emergence of scripted propaganda signifies a larger transition towards centralized ideological governance, wherein the CCP aims to “speak with one voice” across all media channels.

The growing volume and inflexibility of scripted content produced by the Party’s Propaganda Department indicate a diminishing space for independent journalism. Even commercial newspapers, previously regarded as relatively independent, now serve primarily as channels for state messaging.

The authors highlight that by broadening the definition of propaganda to include non-ideological content, the CCP leverages the media to promote its perspective, control information dissemination, and stifle dissent. Scripted articles about disasters, public health, and crime are used to craft narratives and prevent different interpretations.

Grasping the workings of China’s domestic propaganda is becoming essential as the nation promotes its media model internationally via projects such as the Digital Silk Road. This study highlights how authoritarian governments can create the illusion of a diverse media landscape while meticulously managing content behind the scenes.

The Chinese government has developed a type of covert propaganda that is widespread, adaptable, and becoming more sophisticated. By blending scripted content into both Party and commercial newspapers, the CCP has fashioned a media landscape that appears diverse on the surface but is highly controlled at its core.

As China increasingly promotes its governance model abroad, grasping how its media system operates is not merely an academic task but a critical geopolitical necessity.

Source: Bitter Winter