A Chinese government crackdown on the minority Muslims in Xinjiang has taken a toll on the community’s religious staff with the imams being most vulnerable to persecution, according to Uighur victims’ families and scholars.

‘Imam’ is a title in Islam given to a religious staff who leads group prayers at a mosque.

Uyghur Hjelp, a Norway-based Uighur advocacy and aid organization, told VOA that Chinese authorities since 2016 have detained at least 518 key Uighur religious figures and imams. The organization says it has found some of the imams, who were previously trained and employed by Beijing, are now sentenced with long prison terms while a few of them have lost their lives in internment camps.

One of the detained imams, Abdurkerim Memet, was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2017, according to his daughter, Hajihenim Abdukerim in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Abdukerim told VOA that Chinese authorities were hiding the whereabouts of her father for years until recently when a local contact in Xinjiang told her of his imprisonment.

The 61-year-old was employed by the Chinese government before his detention to lead prayers at a neighborhood mosque in Yengisar county in Kashgar city in southern Xinjiang. His family rejects the Chinese government accusation that he was spreading extremism among the Uighurs.

“My father is a peaceful and law-abiding religious figure,” said Abdukerim, adding that her father was salaried by the Chinese government until late 2016 when the newly appointed Communist party chief, Chen Quanguo, began to further enforce Beijing’s rule over Xinjiang where, according to the U.N. estimates, over a million Muslims could be held in internment camps.

“I had never imagined him being imprisoned for serving the community. In these years, I have been only hoping to hear from him again,” she told VOA.

In April, a spokesperson for China’s Xinjiang autonomous government, Elijan Anayit, accused the U.S. officials and media of spreading “rumors” about the detention and prosecution of Uighur imams.

Anayit, in an interview with China Global Television Network, said the Chinese government has attached “great importance to the cultivation of Islamic clergies.” He said the government has subsidized Islamic schooling, including Xinjiang Islam Institute which has over 1,000 students throughout its eight branches around the region, including in Ili, Urumqi, Hotan, and Kashgar.

“The criminals who have been prosecuted are neither religious personages nor religious staff. They are criminals who spread extremism and engage in separation, infiltration, sabotage, and terrorist and extremist activities under the banner of Islam,” said Anayit.

However, some experts say Chinese officials are increasingly using religious extremism charges to gain a free hand in their campaign against Uighurs and their religious leadership.

“These crimes have become so vague even before Chinese law,” Rian Thum, a historian of Islam in China at the University of Nottingham, told VOA.

“They created a long list of illegal religious activities, most of which are not actually illegal things to do in other contexts. For example, to pray at a mosque that is not your hometown mosque can be an illegal religious activity,” Thum said.

Pursuing imams as the main targets in Xinjiang should not come as a surprise, charged Abduweli Ayup, the founder of Uyghur Hjelp.

“They are people who can lead, organize, and mobilize Uighurs in large numbers, and mosques are the only places where Uighur language was kept intact,” he added.

Ayup said the Chinese government was giving the imams salaries ranging from 600 to 5000 RMB before its clampdown campaign in Xinjiang. The detention, he said, is a part of a larger attempt by the Communist party to prevent a flourishing Uighur identity and culture.

No one is immune

The cases of arrest against government-employed religious leaders reveal that even those who have rose through the ranks of the Chinese system are not protected from persecution, according to Timothy Grose, a professor of China Studies at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology.

Locking up the clerics is an effort to sever “the inter-generational transmission of religious knowledge among Uiyghurs,” Grose told VOA.

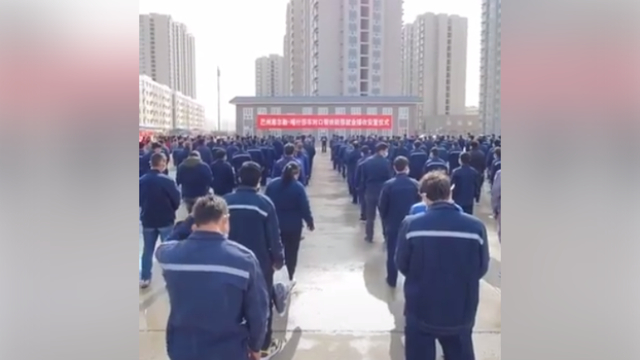

According to Gene Bunin, the founder of Xinjiang Victim’s Database, a website dedicated to collecting data information on detained indigenous residents in Xinjiang, the estimated number of arrested imams among some Turkic communities in the region could be up to 50%. Most of them are taken to the detention camps described by Chinese officials as “vocational training centers” set up to de-radicalize people and teach them new work skills.

“For the reported Kazakhs, imams are about 50% of the victims. For Uighurs, it’s very few, up to 10%,” Bunin told VOA, adding that the number of detained Uighur imams could be much higher.

While imams living in Xinjiang remain most exposed to the Chinese government campaign, those outside are not immune. Families of some Uighur religious figures claim they were possibly tricked into returning to China under false promises.

False promises

Meryemgul Abdulla, a Uighur based in Turkey, told VOA that her husband and a religious scholar, Abduhalik Abdulhak, were arrested after returning to China under the false pledge of allowing him to build a museum.

Abdulhak, a 48-year-old father of five from China and a former graduate of Islamic law from Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, also worked as a businessman in addition to being a religious leader in his community.

Abdulla said Abdulhak returned to China in March 2017 after receiving a message purportedly from his brother that his long-awaited application to establish a museum in commemoration of his great uncle and prominent early 20th century Uighur poet, was approved by local authorities in Turpan city in Xinjiang.

“Soon after he arrived in China, he was taken to a concentration camp in Turpan,” Abdulla told VOA. “I have had no news of him since.”

Source: VOA