A fascinating study by Timothy Grose shows how the “Three News” brutal campaign in Xinjiang is transforming domestic spaces to eradicate Uyghur identity.

I learned long ago from Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987) how important are homes’ architecture and decor to shape an identity. Freyre turned on its head the Marxist argument that material culture is a by-product of class and ideology. It is, he argued, the other way round. How you live your daily life, the house you live in, the furniture, all this shapes who you are and what you think.

In practice if not in theory, Communist regimes have also acknowledged that this is the case. The horrible Soviet-style housing blocks still surviving in Eastern Europe are not ugly because Soviet architects were incompetent. On the contrary, some of them proved elsewhere to be quite brilliant. Soviet apartments were built with the purpose to force those who lived there into the Procrustean bed of uniform conformity to the image of the new Soviet man, “homo sovieticus.”

A new study by Timothy Grose, a professor of China Studies at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Haute, Indiana, shows how the same logic is at work in Xinjiang today. In an article just published in the academic journal Ethnic and Racial Studies (unfortunately, you need to pay $45 to read it), Grose starts from a context where the CCP is eradicating all expressions of Uyghur culture, from language to religion. Millions of Uyghurs are detained in the dreaded transformation through education camps, and one million of Han Chinese “relatives” have been sent to live with Uyghur families to keep under surveillance and “reeducate” them at home.

Not only CCP male “relatives” – who, as Rushan Abbas recently told our readers, often end up sleeping in the same bed with local Uyghur women, whose husbands are in the camps – enter Uyghur homes. The Party also wants to deal with the homes themselves.

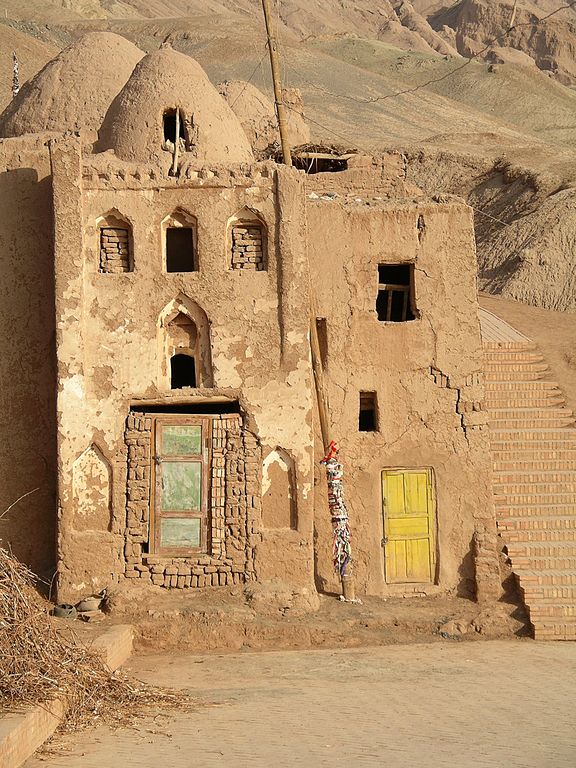

Grose focuses on the planned destruction by the CCP of the traditional Uyghur house, whose center is the supa, an Uyghur word equivalent to the Chinese kang (炕). The supa is a platform raised 40-50 cm. from the ground, built out of earth or lumber. Uyghur families and their guests sit, eat and perform religious ceremonies such as naming ceremonies, circumcisions, and the exchange of marriage vows on the supa, which, Grose argues, “blurs divisions between the sacred and the profane.” Precious carpets cover the supa and the spaces nearby. In some Uyghur homes, there are also merhab niches indicating the direction of the Mecca and used for storing religious articles, editions of the Quran, and bedding items. Some supas, just as the kang, have interior cavities used for heating, and Uyghurs sleep there.

The internal architecture of the houses and the family life converges on the supa, with a concept different from the clear distinction between a living and sleeping area in Western homes. In turn, Uyghur homes converge around the local mosque, and this is precisely why the old city of Kashgar, the heart of Uyghur culture, has been destroyed, as we reported last month.

Grose chronicles how the supa-centered home arrangements are being systematically dismantled in Xinjiang. Supas and of course merhabs disappear, and Uyghurs who try to resist are branded as “extremist” and deported to the transformation through education camps. Traditional furniture is replaced by standardized, Ikea-style tables and chairs. If reforming the house is impossible, it is simply razed, and the Uyghurs moved into apartment blocks.

All this is carefully planned and justified by ideology. Supa is denounced as the symbol of Uyghur backwardness, although non-Uyghur and non-Muslim Chinese also use the similar kang (but a campaign against it is on its way too). Xi Jinping has launched a program advocating “Three News”: new lifestyle, new atmosphere, new order. Grose quotes comments by a government bureaucrat in Xinjiang translating the “new lifestyle” into “thank the Party, listen to the Party, and follow the Party,” and “eliminate the four activities,” by which he means Muslim naming ceremonies, circumcisions, weddings, and funerals. This is calls “leading the rural masses to a secular lifestyle.” “New atmosphere” requires eliminating traditional houses and “strange clothing,” and a “new order” should “never allow religion to intervene in administration, justice, education, or family planning.”

Implementing this campaign, traditional Uyghur homes are being destroyed or restructured, eliminating supas, imposing three separate spaces for “living, growing, and rearing,” and filling the rooms with cheap Western-style furniture, including coffee tables and sofas. By 2018, 300,000 Uyghur homes had been “reformed.” Han CCP “relatives” stay in the homes to make sure that the new order will be respected and to “transform the thinking” of the Uyghurs, through what the Party calls “four commons, four gifts” strategy. This means that the CCP “relatives” should “eat, live, work, and study” with the host Uyghur families, and give them the “gifts” of Chinese kindness and knowledge of CCP policy, law, and culture.

There is harsh punishment for those Uyghurs who would not cooperate. Party cadres inspect the homes and give them a red banner if they are properly “modernized” and “sinicized,” and a black banner if they are not. A black banner is a serious matter. Families who receive a black banner thee times are seized and “paraded on stage” in front of the other villagers, where they should make amend and “promise to rectify their faults,” in the style of the Cultural Revolution.

Although, as Grose notes in conclusion, the Three News campaign is so unpopular that resistance is generated, destroying the traditional Uyghur home is another key passage in the cultural genocide. As Magnus Fiskesjö, a professor of Anthropology at Cornell University, recently wrote commenting the cultural “genocide with Chinese characteristics” in Xinjiang, “given what is happening, can China remain represented in any international bodies for cultural heritage protection? UNESCO? Or can their representatives expect any respect? I think not.”

Source: Bitter Winter

英语-20210131-GY-RGB-scaled.jpg)