Ruled by the totalitarian government, the Chinese are suppressed for any word that the regime deems as damaging its image.

by Li Mingxuan

China’s President Xi Jinping and his regime don’t tolerate the slightest criticism, even when their mistakes are apparent. In the latest mass crackdown on dissent, many were heavily punished for expressing dissatisfaction with insufficient measures under Xi Jinping’s “personal leadership and guidance” to stop the spread of the coronavirus epidemic. Among them is Xu Zhiyong, a constitutional scholar and rights activist, who was arrested after he had gone into hiding for criticizing Xi Jinping for his policies. Professor Xu Zhangrun from Tsinghua University was placed under house arrest for calling Xi Jinping “shameless.”

Even a comment online can land you in jail in totalitarian China. In July 2018, a dozen or so police officers in the southeastern province of Fujian raided a man’s home and arrested him for saying on Weibo, a Chinese microblogging platform, that “Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption work only cures the symptoms, not the disease,” and that “Xi Jinping’s clique is very corrupt.”

When his relatives went to visit him in the detention center he was kept in, they were told that the man could not be visited because his remarks are unfavorable to Xi Jinping and “constitute political issues.” Guards at the detention center also remarked that hiring a lawyer for him was useless.

Another netizen from Fujian was arrested and detained for two months for posting on Weibo in June 2018, “Our national leaders do nothing practical, but only do some superficial work.” During his time in detention, guards often incited other inmates to beat him, resulting in internal injuries and a concussion.

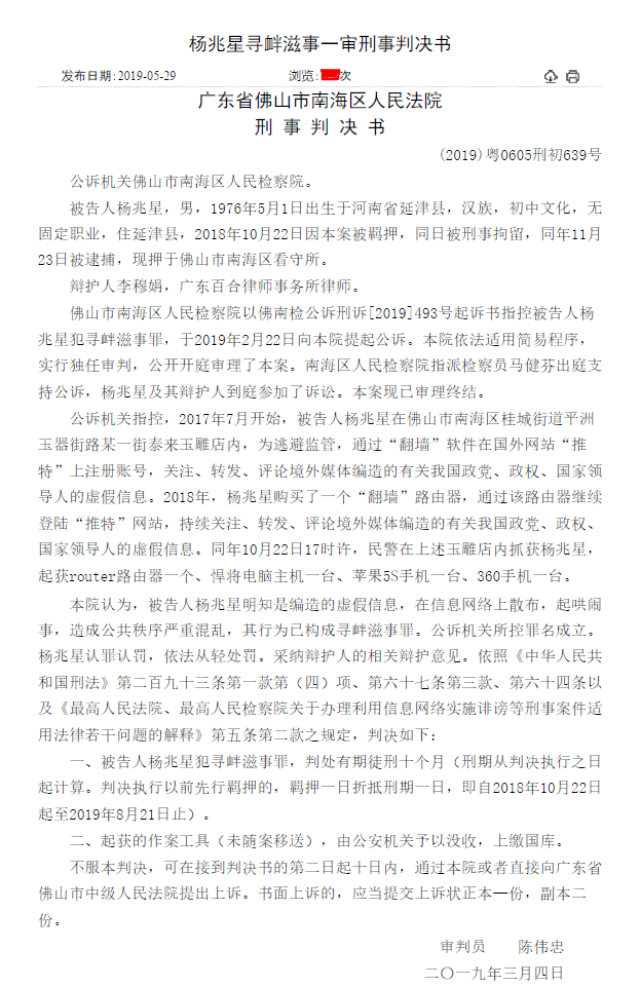

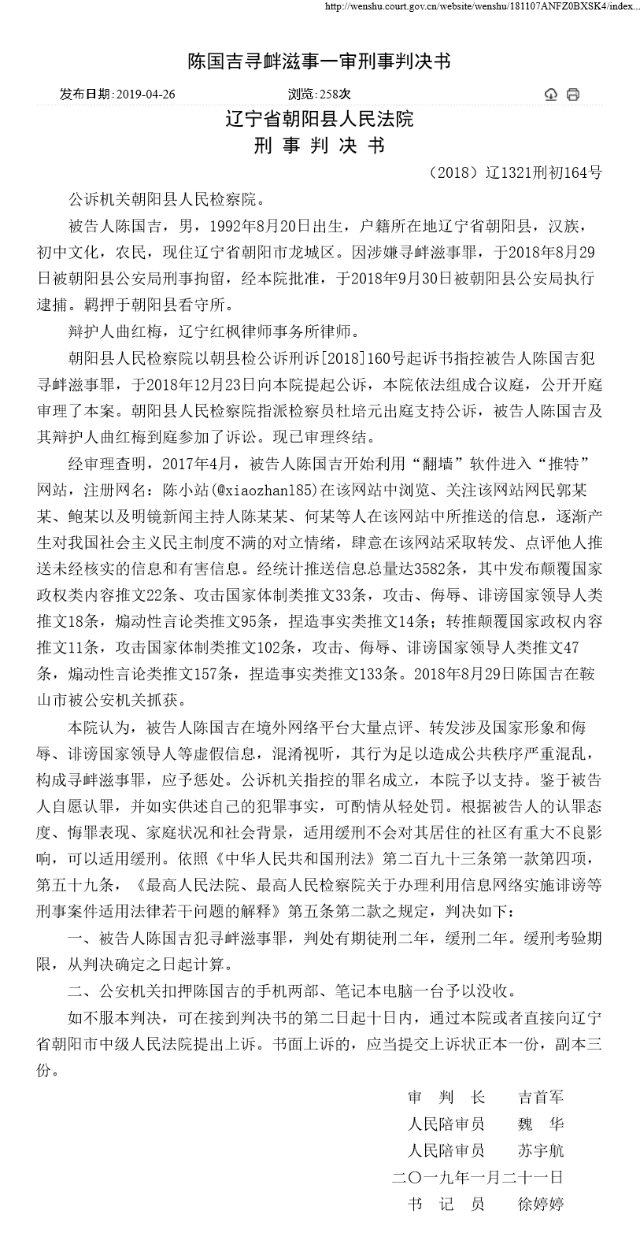

Using internet censorship circumvention tools to post comments overseas about the CCP’s leaders will get people into trouble with authorities as well. Twitter user “中国文字狱事件盘点(@SpeechFreedomCN)” posted online the verdicts of two convicted men. One of them, Yang Zhaoxing from Yanjing county in the central province of Henan, was sentenced to ten months on March 4, 2019, for bypassing the Great Firewall of China to comment about China’s regime and its leaders on Twitter. Chen Guoji from Chaoyang county in the northeastern province of Liaoning was sentenced to two years in prison and two years’ probation for posting on Twitter information deemed as “subversion of the state power, attack on the state system and leaders, and remarks of incitement.”

Police officers and censors in China continuously monitor information online, looking for any expression of dissatisfaction with the government or criticism of its leaders. “The CCP strictly controls every word; no one cannot speak the truth, especially if it is written. The government catches and punishes you,” a netizen from the northern province of Hebei said.

He posted in his group on WeChat, the dominant chat platform in China, at the end of last year, “This government is inferior to the previous one. There is something wrong with its policies. Now it’s hard for people to earn money, and prices of goods have gone up.” Two days later, he was detained for 15 days on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” and was fined 1,000 RMB (about $ 140).

A worker from the northern province of Shanxi was detained at the beginning of 2019 for posting on WeChat, “The Chinese government is corrupt and unfair. There are no human rights in China.” This and other messages about “democratic and free life overseas” were blocked shortly after they were posted. Two months later, the police in another province where he worked arrested and detained him for ten days, accusing him of “inventing stories and disrupting social order.” His ID card and phone were taken away.

According to a source, during his detention, police officers punished him by making him sit straight for a long time and sing patriotic songs and recite “The Standards for Being a Good Pupil and Child,” Di Zi Gui (弟子規) in Chinese, an ancient manual based on the teachings of China’s most influential philosopher Confucius (551-479 BC) on how to be a good person. If he couldn’t memorize them, he was not allowed to sleep.

“There is no justice or democracy in China, which is ruled by a dictatorial regime. If the system doesn’t change, it’ll only incur more hatred from citizens, and the CCP will come to its end,” said a netizen from Shanxi Province.

Source: Bitter Winter