Accounts by four teachers who witness daily CCP’s destruction of Uyghur culture and language, psychologically torturing Uyghur youth in the process.

by Xiang Yi

Bitter Winter met with four ethnic Han teachers who work in elementary and middle schools in various parts of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. They recounted in detail how the CCP is repressing Uyghurs, even the very young, by prohibiting them from speaking their native language, destroying books, and forcing children to swear allegiance to the state that incarcerates their parents just for being Muslim.

Eradicating the Uyghur language

Ms. Zhang, a teacher at an elementary school, told Bitter Winter that last year, her school mobilized the faculty and students to report anyone who speaks the Uyghur language on campus: every teacher was required to submit the names of at least ten students. If they didn’t complete the task, they would be given overtime work as punishment. Meanwhile, the CCP committee branch at the school issued a list of all Uyghur teachers to the teaching staff, requiring to mark the names of those who speak Uyghur regularly and submit the list to the administration of the school.

“The school principal emphasized during a staff meeting that the struggle with ‘two-faced persons’ is endless. If someone holds a bowl of rice [a Chinese slang referring to the job one relies on to support the family] that was given by the state but still speaks Uyghur, then he/she is a typical ‘two-faced person.’ The school authorities have promised the government that the Uyghur language will no longer be spoken on campus. Anyone who makes mistakes won’t have an easy time!” recalled Ms. Zhang. “Seeing the nervous looks on Uyghur teachers’ faces, I felt an inexplicable pain in my heart. Reporting and telling on each other, without the need for evidence, is no different from ‘white terror,’” the woman added, referring to arrests and executions of suspected dissidents in Taiwan between 1949 and 1992.

Not long after the meeting, a teacher was criticized publicly for speaking Uyghur in the teachers’ office, and an Uyghur student who said a few words in Uyghur during a break was forced to attend intensive Mandarin classes. Another student who was overheard speaking Uyghur had to write “I will speak Mandarin” 4,000 times in a notebook as punishment.

In another instance, Ms. Zhang remembered, the school punished the whole class, making them stand outside the classroom and repeatedly shout ‘I will speak Mandarin,’ because the administration previously learned that a few in the class had spoken Uyghur but could not identify who exactly. Some aggrieved children told Ms. Zhang that no one in the class spoke Uyghur, and the teacher who reported them must have mistaken their dialect with the Uyghur language.

Since the measures were enacted in the school, Uyghur teachers and students became extremely cautious, making sure that not a word of Uyghur slips from their mouths in classrooms, dormitories, cafeteria, or going to and from school. Ms. Zhang believes that because of the measures and imposed punishments, the school has become a version of a transformation through education camp.

“Even when filling out a straightforward form, students kept asking me whether they were doing it correctly. My heart bled when I saw how cautious they were, as if they were skating on thin ice,” said Ms. Zhang. “They are fluent in their ethnic language, but they aren’t allowed to speak it and, instead, are forced to speak awkward-sounding Mandarin. Students who don’t speak Mandarin well stopped speaking at all. When I see their helpless and depressed looks, I ask myself: who can save them?”

“The school is so good to me!”

Another teacher, who works in a middle school in the region, reported that she and some other colleagues in the school were assigned “an important political task” to keep an eye on the students whose parents are detained in transformation through education camps.

All the assigned teachers received the Assistance Handbook, issued by the Bureau of Education. The Handbook, that has the Chinese word for “secret” printed on the first page, requires to register information about the students, their “abnormal” thinking and emotional state, as well as information about their families, and the reasons for their parent’s detention, and report all this to the Bureau of Education.

Some schools have even demanded children to write letters to their parents detained in camps that include their pledge to obey and follow the Communist Party and be grateful to it. “It’s really ironic. Students are required to write letters to their parents without knowing their whereabouts or when they will return,” the teacher told Bitter Winter.

When one of the students asked the teacher, who herself has a son, just over ten-years-old, why he needed to thank the Party in a letter to his parents, the teacher didn’t know how to answer him. “My parents have been arrested, and I don’t know when they can get out, but I can still be educated at school. The school is so good to me!” the teacher quoted an excerpt from the said student’s letter.

She said that the student had changed after he had to write the letter: the well-behaved boy suddenly became disruptive, he would sneak out to play during afternoon naps or disobey in other ways – something he had never done before. “I didn’t rebuke him. After all, such thought control is very stifling,” the teacher said. “It’s so cruel to make these children thank the same government that arrested and harmed their next of kin. Such things are devastating to their psyches.”

All books in Uyghur confiscated

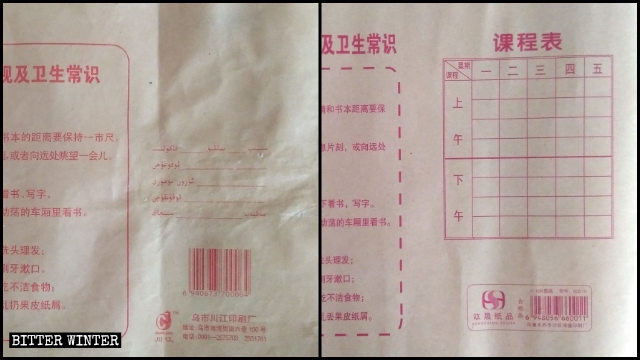

A teacher from northern Xinjiang told Bitter Winter that last September, his school demanded to remove from the school all Uyghur-language books. Also, all religion-related texts and images, like mosques, crosses, and the crescent moon and star symbol, in books were required to be destroyed.

Students were ordered to tear up the books, one after another. Their parents got rid of all publications with religious connotations at home, fearing that they could be sent to transformation through education camps if such books were discovered.

In November, the teacher received another notice from the school administration, this time, demanding to blot out any reference to religion in children’s books, like Aesop’s Fables or Grimms’ Fairy Tales. Besides, all teachers in the school were ordered to take part in a political study meeting. Among other things, the teachers had to watch Conspiracy in the Textbook – a CCP-created documentary about Sattar Sawut, the former head of the Education Department in Xinjiang, and other officials and intellectuals, who were given death penalties or sentenced to life in prison for “compiling Uyghur textbooks that willfully distort history and have reactionary content.” As per CCP’s propaganda, the convicted “didn’t hesitate to extend their devilish claws to the Uyghur youths and use the textbooks to poison the young people’s thinking in order to achieve their evil goals.” The documentary is often shown across Xinjiang as a form of intimidation.

Children in the school are also made to swear an oath of allegiance to the Communist Party and China’s leadership, the teacher said. Students are usually gathered together and follow a teacher in reciting the pledge or read it aloud themselves. Though its content may differ from school to school, the text is pretty much the same: “Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, I swear to resolutely follow the Communist Party, not to uphold any religious beliefs, fight against the three evil forces [separatism, terrorism, and religious extremism], and stay away from “two-faced” thoughts.”

“I sometimes notice children on the street who stop automatically and raise their arm in a solemn salute when they hear the national anthem,” the teacher said. “Perhaps that is exactly what the CCP wants.”

Students and children feel stifled

An elementary school teacher from southern Xinjiang secretly helps her Uyghur students to avoid punishments imposed by the administration. Trusting her, some children confided in her that they were having a hard time in the school because they felt stifled and found the intensive language classes extremely difficult.

“We’re under supervision from morning to night and are required to speak Mandarin only. We’re not machines. It’s too exhausting,” the children complained. “If we quit school, this would cause trouble for our parents.”

The teacher feels stifled herself. But not only because of the harsh political environment, but also due to the deep-seated pain that her conscience emanates.

The schools may look ordinary and friendly on the surface, but in fact, they are destroying ethnic culture and eliminating freedom of a people under the pretext of “compulsory education.” The teacher thinks that in these schools that have become similar to transformation through education camps, innocent children are victims of their ruler’s ambitions.