Some hoped that with the new religious law, which was finally signed on August 26, 2017, and came into force on February 1, 2018, there would have been less control over religion. In fact, things went from bad to worse.

Some hoped that with the new religious law, which was finally signed on August 26, 2017, and came into force on February 1, 2018, there would have been less control over religion. In fact, things went from bad to worse.

by Massimo Introvigne

The new Religious Affairs Regulation, the main law on religion in China, was drafted between 2014 and 2016 by the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA). In 2016, SARA circulated a draft to leaders of state-approved religions, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) legal and religious experts, and various governmental offices. Having collected their feedbacks, a revised draft was sent to the State Council, which on September 7, 2016, published it and invited comments from the public. Some Christian leaders sent quite negative comments, but they were largely ignored. Worse, the final text is arguably even more restrictive than the draft. The State Council approved the final version on June 14, 2017. Premier Li Keqiang signed it into law on August 26, 2017, and it came into force on February 1, 2018. Detailed enforcement provisions should still be enacted. It has been announced that the management of religion should gradually pass from SARA to the United Front, but this has not yet happened.

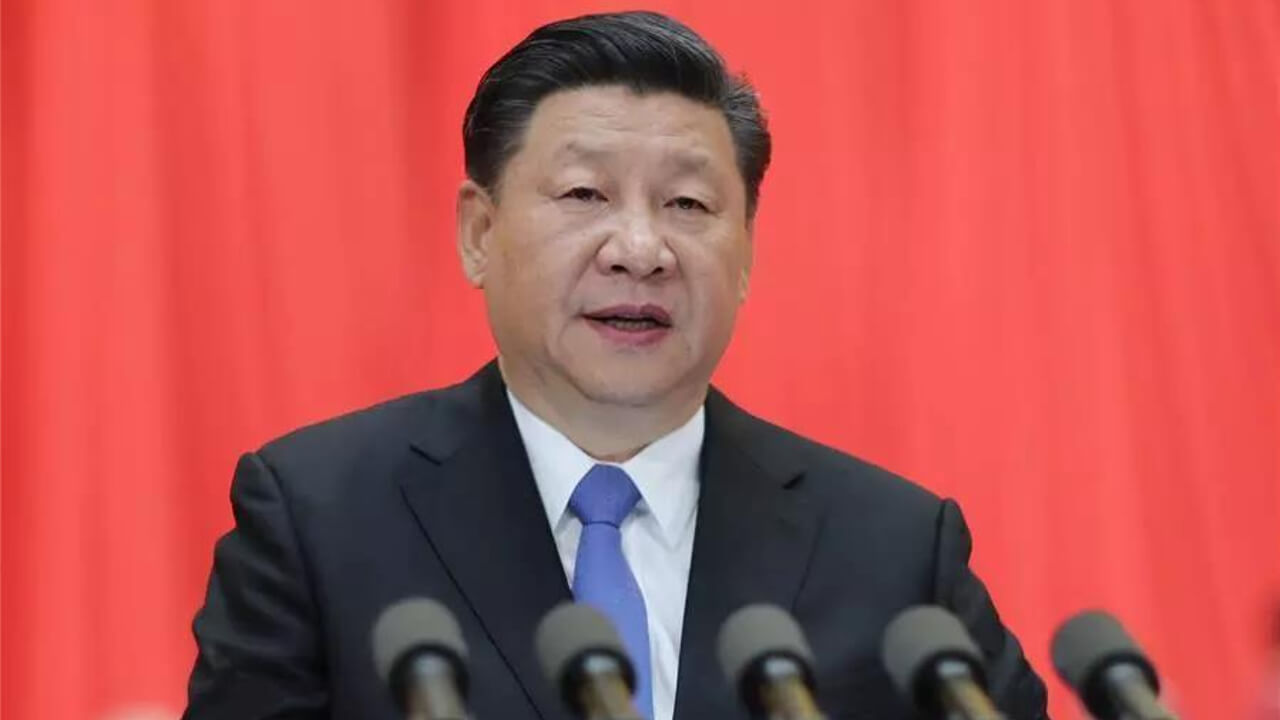

Why did the CCP decide that it needed a new law on religion? Basically, this is a consequence of the ascent of Xi Jinping, who became general secretary of the CCP in 2012 and president of China in 2013. In previous weekly features of Bitter Winter, we have discussed what sociologist Fenggang Yang called the three markets of religion in China: the red market of government-controlled religions, the black market of the groups proscribed and persecuted as xie jiao (“heterodox teachings”), and the gray market of everything that is in the middle. The red market was revived after the Cultural Revolution, which had tried to eradicate religion altogether when Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997) concluded that religion was there to stay and coined the slogan of the “mutual adaptation between religion and socialism.”

Xi Jinping takes a very active interest in religion, and his approach is different from Deng. He sees religion as a problem of national security, and its solution to this problem is “sinicization,” defined as “the submission of religion to socialism and the CCP.” There is no “mutual adaptation” any longer. Only religion should adapt itself to the CCP rule. Xi is aware that a large part of the Chinese religious market would not adapt. His security approach calls for harsh suppression and persecution of all forms of religions that would prove not to be “soluble” into the CCP.

Xi Jinping is also quite secretive in its management of religion. It is believed that the key document outlining the new strategy is Document no. 16 of 2016, which is connected with a speech Xi gave at the National Conference on Work in Religion, held in April 2016. However, both Xi’s speech and Document no. 16 are classified and kept secret.

On the other hand, the new law on religion obviously implements Xi’s directives and Document no. 16, whose content may be inferred from the law itself. Voices that the new law would have actually relaxed the pressure on the gray market were circulated before 2016 in some Christian circles but were simple disinformation. In fact, the same Fenggang Yang has analyzed the new law by applying his theory of the three markets, and concluded that Xi’s aim is to destroy the gray market, particularly its segments including the Protestant house churches and the Buddhist and Taoist temples that exist outside the official red market national associations (the question of Islam is more complicated and should be discussed separately).

Yang explained that, when he proposed the theory of the three markets in 2006, he regarded the Protestant house churches as part of the black market. They were, after all, illegal. However, in 2012 Yang revised his theory and included the house churches in the gray market, since they were not persecuted as harshly as the xie jiao and were allowed at least a precarious existence. Now, with the new law, Yang believes that President Xi is trying to compel the house churches and the unregistered Buddhist and Taoist temples to make a choice: either they join the red market (which for the house churches means joining the government-controlled Three Self Church) or they will be pushed into the black market and persecuted as xie jiao. Yang believes that the Christian house churches will resist and Xi’s plan will fail. But that this is his plan, he has no doubt.

This is the key to understand the new law. Its aim is not to offer new spaces of tolerance, but to eradicate the Christian, Buddhist, and Daoist segments of the gray market, compelling the underground Catholic Church (which is also part of the gray market) to merge with the red market Catholic Patriotic Association through an agreement with the Vatican. Islam will be controlled in different ways.

The provisions of the law through which Xi’s strategy is being implemented can be divided into four groups. First, with provisions in part not included in the 2016 draft but which surfaced in the 2017 final text, the law solemnly proclaims that religions should “implement core socialist values” (art. 4, no. 2). There is no room for religions that would not be ready to preach socialism and CCP ideology. Second, there is an expanded, if vague, definition of “religious extremism,” possibly imported from Russia. “Propagating, supporting and funding religious extremism” (art. 4, no. 4) is severely punished and may lead to treating as xie jiao religious communities not included in the list of the xie jiao. Third, there are stringent rules for constructing new places of worship. And one of the most dangerous parts of the law is the one allowing the use of premises different from churches, mosques, or temples as “temporary religious venues” only with the explicit approval of the CCP (art. 35). This has led, for example, the landlord company that was renting a floor of a building in Beijing to Zion Church, a large gray market house church, to cancel the contract on August 20, 2018. The contract was extremely profitable for the landlord but renting premises different from a church to a religious group is now forbidden if not explicitly approved by the CCP as a “temporary” measure. In the case of the Zion Church, the rental agreement was with Beijing Jianweitang Culture Co., Ltd, a cultural company incorporated by members of the Zion Church, but that non-religious entities rent spaces for religious worship is also forbidden by the new law. Fourth, there is a strict prohibition on traveling abroad for religious purposes, or operating religious schools in China, for groups that are not part of the official red market (art. 41).

There are several other limitations, but these are the most effective and show the attempt to eliminate the gray market gradually. But there is more. Even religious communities in the red market see their situation worsened. They are under control for their effective promotion of “socialist values” and CCP ideology and are warned that existing regulations would be strictly enforced. This includes the features and architecture of the places of worship, and the strict prohibition against minors from entering them. Fenggang Yang believes that the regulation also aims at examining the red market communities, checking out what are really “sinicized” and preaching “socialist values” and, particularly in the Three-Self constellation, “push some churches in the red market into the black market.”

Religions hit by the new law hesitate between compliance and resistance. Compliance may lead to sweet and slow euthanasia of religion. Resistance – to harsh persecution. At any rate, there are no improvements in the situation of religion in China. With the new law that came into force in 2018, things went from bad to worse.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist and intellectual property consultant. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of tens of books and articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. And of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. He is also a consultant on intellectual property rights. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). In June 2012, he was appointed by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs as chairperson of the newly instituted Observatory of Religious Liberty, created by the Ministry in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale. http://www.cesnur.org/

英语-20210131-GY-RGB-scaled.jpg)