In a nationwide drive, place names are purged to reflect “excellent traditional Chinese culture” and show the country’s resistance to the “worship of foreign things.”

by Shen Xiang

At the end of October, a diner in Jinzhong city in the northern province of Shanxi posted a notice on its window reading, “Tired of rectification. Tired of business.”

The owner of the diner, which had been named “American California Beef Noodles” since its opening, was ordered twice to rename his business because it bore foreign names. In August, government officials forcibly removed the word “American” from its signboard. The owner then changed the sign to “Etonda California Beef Noodles.”

In October, however, the new signboard was again removed because of the word “California.” The owner said that the replacements of signboards have resulted in substantial financial losses for him.

In July, the “Specialty Store of German Kräuterhof Dietary Supplements” in Bayannaoer city in Inner Mongolia was compelled to remove the word “German” from its signboard. As a result, the store suffered a decline in sales since customers started doubting the quality of products after the removal of the word “German.”

The nationwide clampdown on foreign names has been carried out following the Notice on Further Crackdown on Irregular Place Names, jointly issued on December 10, 2018, by several central government institutions, among them, the Ministry of Civil Affairs, Ministry of Public Security, and State Administration for Market Regulation. According to the notice, any name for public places, businesses, and residential communities deemed to “worship foreign things,” “deliberately exaggerate the reality,” or “promote feudal superstition” is targeted for rectification.

The document also states that “as one of the primary political tasks deployed by the central government, the work to control and remove irregular names for places should be an inevitable requirement for inheriting and protecting excellent traditional Chinese culture and solidifying cultural confidence.”

The use of Western words in the names of businesses and residential communities in China increased in the 1990s as a means to indicate a more upscale way of life. Chinese sociologist Guo Yuhua believes that respect for the West in China was also a natural response to the gap between the country and the Western world after China’s opening up reforms.

Chongyang meiwai (崇洋媚外) — the “worship of foreign things” – was considered a crime during the Cultural Revolution. People could be convicted even for having relations overseas. Gou Yuhua thinks that the current regime is “doing it again and further tightening the control of the official ideology only because of their worsening relationship with the West.”

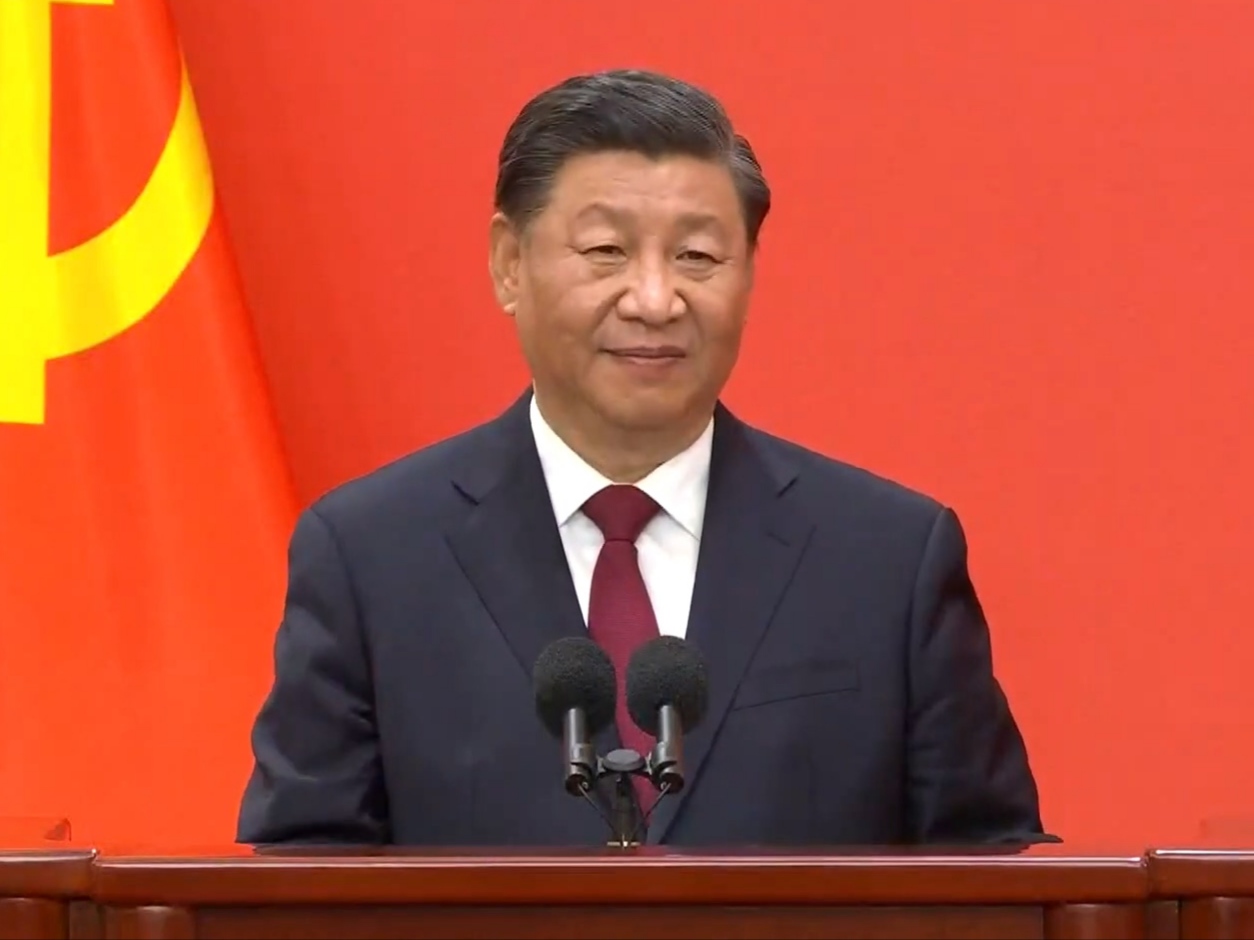

The spread of the anti-Western sentiment has accelerated after President Xi Jinping launched his policy of “sinicization,” as the promotion of traditional Chinese culture and all things Chinese gradually penetrated every aspect of society. The suppression of the “worship of foreign things” is now also used to instigate nationalism and anti-foreign attitudes.

This is especially evident amid the ongoing US-China trade war and pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, which the regime presents to the Chinese public as being “backed by foreign forces.” Next to the expansion of religious groups and movements in China, the CCP treats the protests as the result of “foreign infiltration.”

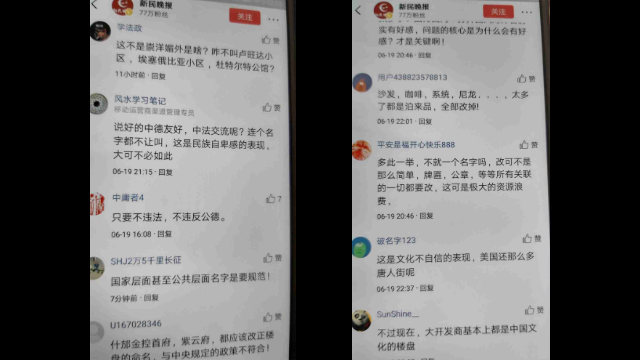

Even in the heavily controlled China’s cyberspace, some voices of dissent express concern that the ban of foreign names and things will not increase the cultural confidence of the population. “Boycotting foreign festivals? Banning foreign names? No exotic clothes? That by no means indicates cultural confidence,” a netizen commented.

The government seems to be determined to eliminate all foreign names across the country, disregarding the distress the changes bring on the population and the cost of the campaign. Its new target – the names of streets and residential communities.

“The old name was harmonious with the style of the entire community. The new Chinese name sounds weird,” a resident from Luoyang city in the central province of Henan told Bitter Winter. His residential community “California 1885” has been recently renamed “Huaqian Tree Community.”

The resident added that the old name was known to public utility companies, postal and taxi services, and the sudden name change is now causing a lot of confusion and inconveniences in the daily lives of residents.

In June, the “Venice Riverdale Community” in Jiangxiang town, administered by Nanchang, the capital of the southeastern province of Jiangxi, was renamed “Ziyang Garden.”

The “Hongkelong British Federal Community” in Nanchang was renamed “Huahao Jincheng” on orders by the community’s CCP branch.

Similarly, several residential communities in Fuzhou, the capital of the southeastern province of Fujian, were forced to change their names. Among them, “Rongxin White House” and “Rongxin City of David.”

For people who run businesses, the changes in names or addresses mean that licenses, signboards, ads, business cards, and alike must also be changed. And this is not cheap, but the government is not compensating these expenses.

The rectification campaign also targets businesses with names related to religion. Like “Canaan Doors and Windows (迦南門窗jianan menchuang)” in Anshan, a city in the northeastern province of Liaoning, has been forced to rename the company to “Fujun Doors and Windows,” and “Longfeng Buddhist Karma (龍鳳緣佛longfeng yuanfo)” to “Longfeng Pavilion.”

Source: Bitter Winter