Arguments and campaigns of the 1920s against Christianity were still used in subsequent decades, from Chairman Mao to Xi Jinping.

by Massimo Introvigne

A key feature of the so called “Xi Jinping Thought” is the superiority of Chinese Han culture on all other world cultures. Not surprisingly, this idea strikes a nationalist chord both in China and in the Chinese diaspora. We can hardly blame Xi Jinping, or others, for being proud of the many achievements of Chinese history, art, or literature. However, as many scholars have noted, Xi often insists that the superiority of Chinese culture is based on its being allegedly unique among the great world cultures in confining religion to a marginal, unimportant role. This theory is, however false. It fails to distinguish between language and reality. Before meeting the West, China did not have a terminology for “religion” and even for “God.” However, most Chinese firmly adhered to beliefs and practices that can only be called deeply religious.

Xi’s theory is not new. It dates back to Chairman Mao, but Mao himself admitted he derived it from intellectual movements of the period between the First and the Second World War, including the May 4 Movement of 1919, the May 30 Movement of 1925, and the Restore Educational Rights Movement of 1924–27. Some historians believe all these movements are part of a larger phenomenon known as “New Culture.” These movements were also complicated. They protested against foreign imperialism and were joined by students and intellectuals of various persuasions. Many of them, however, blamed China’s weakness on the backward influence of traditional religion, which was declared as a minor, inessential part of Chinese culture, to be replaced by progress and science. The West was criticized for its imperialist treatment of China, yet at the same time it was admired for its economic and scientific achievements.

The problem, for those among the New Culture intellectuals who were more critical of religion, was that the achievements of the West seemed to be obviously connected with Christianity.

Some concluded that Christianity was indeed a potential ally for modernizing China. For example, Chiang Kai-shek (1987–1975) came to embrace a sympathetic view of Christianity and ended up converting to Methodism. Others, however, took from European secular humanists the idea that the West had become genuinely progressive and prospered only when its ruling classes largely abandoned Christianity.

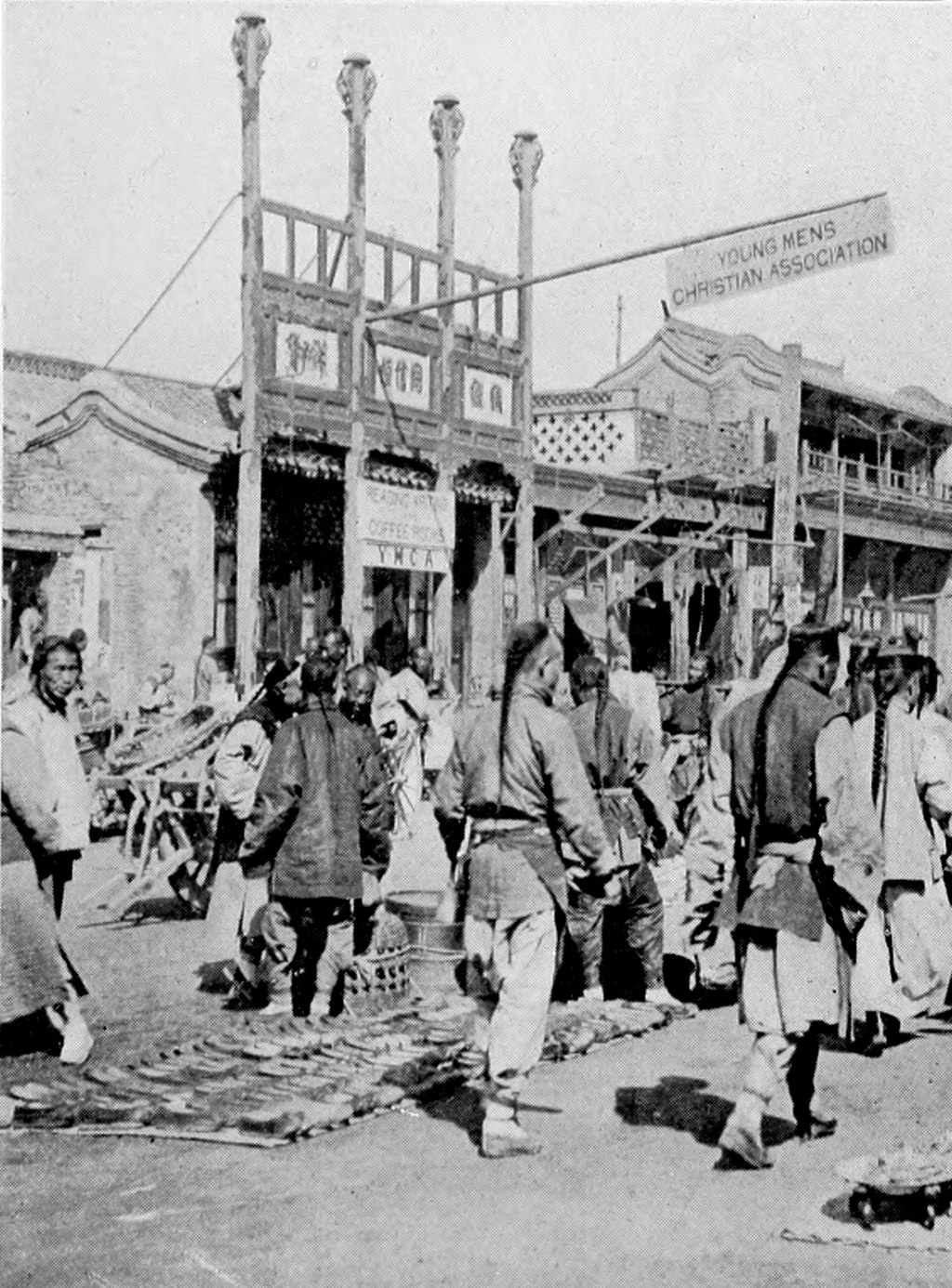

The conflict between the two wings of the New Culture movement erupted in 1922. Pro-Christian reformist Chinese intellectuals welcomed the decision by the World Student Christian Federation, which had been founded in 1895, to hold its international congress at Beijing’s Tsinghua University. The anti-Christian wing reacted by founding, on March 9, the Anti-Christian Student League (非基督教学生同盟).

The League’s principle was that “Christianity and the Christian Church have created many evils in the history of humankind” and have supported the ruling classes against the poor. “We declare, the League stated, that Christianity and the Christian Church today, demons that aid the merchants to do evil, are our enemies. We must battle against them in a war to the death.”

Although it expanded to some twenty Chinese cities, the League remained particularly strong in Shanghai. In Beijing, it became part of the Great Anti-Religious Federation, which was against all religions, not just Christianity. As American historian Jessie Gregory Lutz noticed (see her “Chinese Nationalism and the Anti-Christian Campaigns of the 1920s,” Modern Asian Studies, 10:3, 1976, 395–416), the Federation was influenced by a tour of lectures in China in 1920–21 of British philosopher Bertrand Russell (1972–1970), a well-known critic of organized religion.

The League did not achieve its immediate aim, as the World Student Christian Federation did come to Tsinghua University in Beijing for its world conference, which duly took place on April 4–9, 1922. The League remained active for a short period only, although it was revived in 1924–27 to support the Restore Educational Rights Movement, which was largely directed against Christian schools. It also translated anti-Christian material from French and English and built a reservoir of arguments against Christianity and in favor of the alleged secular character of the higher Chinese culture, which was later exploited by Chairman Mao and its successors, up to Xi Jinping.

The first Western historians who paid some attention to the Anti-Christian Student League emphasized that it included opponents of Christianity of different ideological persuasions, and referred to the European traditions of Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and positivism. More recent scholarship, however, has emphasized that not only it ultimately benefited the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) but was largely infiltrated by it. As C. Martin Wilbur and Julie Lien-ying How have argued in their book Missionaries of Revolution (Harvard University Press, 2014), agents of the Soviet Union also played a role.

The Anti-Christian Student League, thus, although short-lived and comparatively unsuccessful, prepared arguments justifying persecutions against Christianity in China for decades to come. It was also a textbook example of CCP infiltration and control of other revolutionary organizations.

Source: Bitter Winter