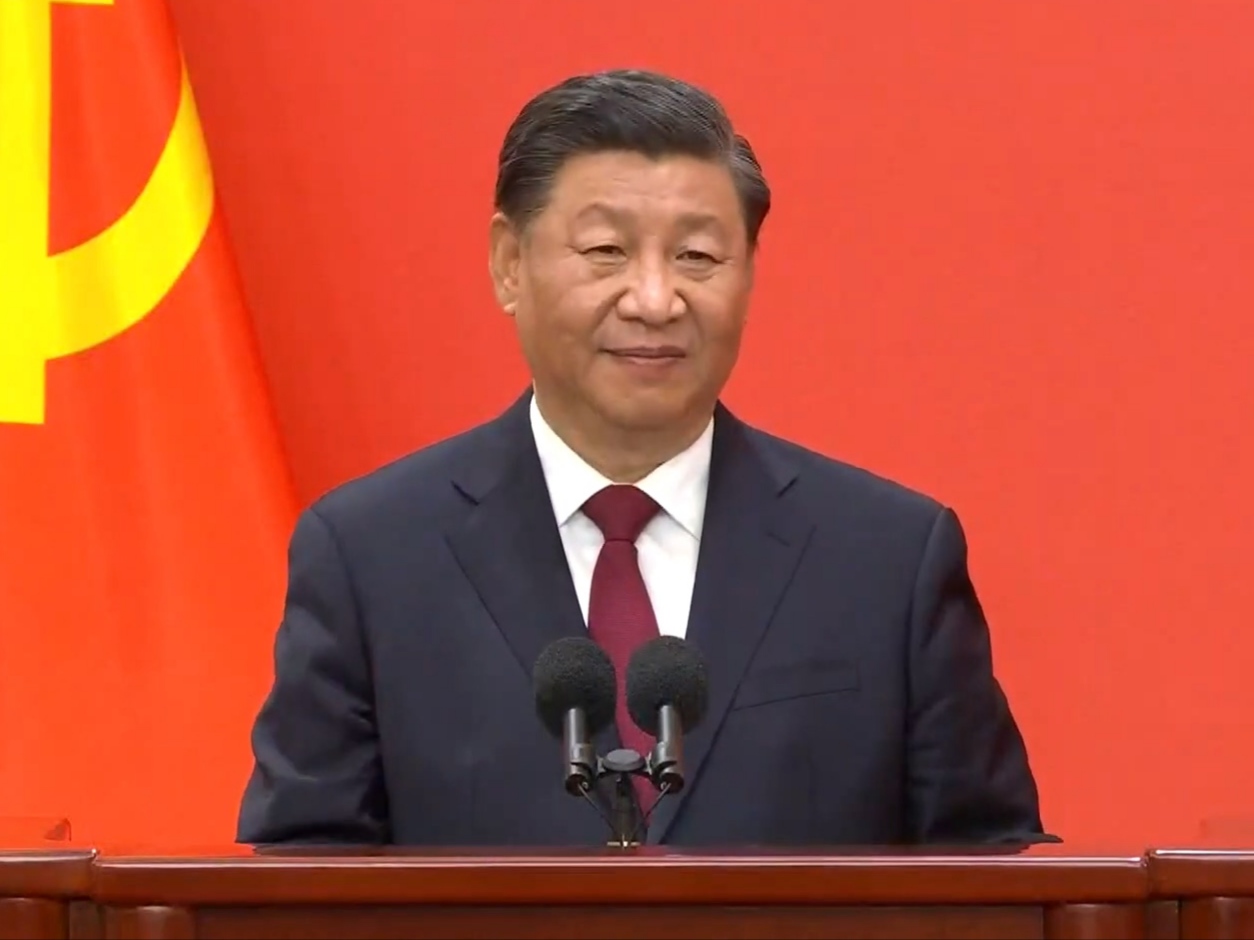

The obsessive campaign to promote the President’s legal ideology continues with the publication of a book collecting his main texts on the matter.

by Massimo Introvigne

Bitter Winter has commented repeatedly on how “Xi Jinping’s Thought on the Rule of Law” is now emerging as the central tool in the attempt to elevate the status of the Chinese President as a Marxist ideologist not less important than Lenin, Stalin, or Chairman Mao. Whether this would work, or Xi will be forgotten after somebody will replace him in China—just as nobody would read today, say, the books signed by Leonid Brezhnev—is an entirely different question.

As part of this campaign, the Institute of Party History and Literature of the Central Committee of the CCP has just published a new book by Xi Jinping. It is titled “On Persistence in Comprehensively Governing the Country According to the Law” (论坚持全面依法治国),and includes 54 texts and speeches by the President on the rule of law, dated between December 4, 2012 and November 16, 2020. Xi Jinping’s previous book, “On the Party’s Propaganda and Ideological Work,” was published just one month before this one—and Party members and high school and college students are supposed to study all of them.

The last chapter of the new book is Xi Jinping’s lecture at the Beijing conference on the rule of law of November 16, 2020. We have already analyzed this text in Bitter Winter, as a clear example of how the words “rule of law” may be misleading. In the Western legal tradition, “rule of law” means that all citizens, including those in the government, are subject to the law. Xi Jinping adopts the Marxist point of view, according to which the celebrated “rule of law” is simply the rule of the bourgeoise over the proletarians, and the Communist revolution solves the problem by subjecting the law to “the People” and its sole authorized spokesperson, the Communist Party. “Xi Jinping’s Thought on the Rule of Law” reiterates that the law should be subject to the CCP, rather than the CCP to the law, but adds a new global twist by arguing that also international law should be subject to the interpretation of a coalition including CCP-led China and like-minded international critics of that annoying bourgeois idea of universal human rights.

By perusing the book, one discovers that Xi did not invent this theory in 2020, but developed it gradually since he came to power in 2012. Of special interest is the chapter “The Party’s Leadership and the Socialist Rule of Law Are Consistent,” in fact a portion of Xi’s speech at the Central Political and Legal Work Conference of January 7, 2014. This text already included a good deal of what Xi would say at the November 2020 conference. We read there that with the Communist revolution, “the People,” rather than capitalists or the bourgeoisie, becomes the master of the law. However, as Marx knew very well, the problem is how to ascertain the will of “the People.” Marx’s answer is that the Communist Party is the only entity that knows what “the People” wants, or at any rate what is better for “the People.”

Xi repeats that “the People is the master,” but the Marxist rule of law can only function “by the Party leading the People.” In a Communist system of the rule of law, “the most fundamental is to uphold the Party’s leadership. Upholding the leadership of the Party means supporting the People to be the master of the country and implementing the basic strategy of governing the country with the Party leading the people.” In other words, “only by adhering to the Party’s leadership, the idea that the People is the master of the country can be fully realized, and the country and social life can be institutionalized and ruled by the law in an orderly manner.” One understands that “the People is the master of the country” and the law should respect the People, rather than vice versa, really means that the CCP is the master of the country, and the law should obey the CCP.

The different chapters tediously apply this principle to the lawyers, the judges, the military courts, the police, the regulatory authorities for the economy, and so on: they should respect the rule of law, which in a Marxist sense means respecting the law as interpreted and dictated by the CCP. By definition, there can be no conflict between the CCP and the law because, based on what Xi calls the principle of the “organic unity of Party leadership,” the CCP is the law, but what needs to be clarified here is that nobody can presume to use the written laws to criticize the decisions and policies of the Party. Otherwise, the rule of law would be used to “weaken and narrow” the Socialist essence of China, while its real purpose is to reinforce it. “There are many things, Xi writes, that need to be explored in depth, but the basics must be adhered to for a long time, i.e., the leadership of the CCP must be adhered to.”

One interesting chapter is a compilation of texts, some of them unpublished, about Hong Kong and Macao, where Xi explains that the principle “one country, two systems” may only be understood as being subject to the rule of law, by which he means the Marxist/CCP rule of law, which makes the laws subject to the Party. And that should perforce include Hong Kong laws.

Another chapter includes an apology for the Constitutional amendments of 2018. The world’s attention focused on Article 45 of the reform law, which eliminated the term limits for the President, meaning that Xi can now be President for life. However, Xi argues that the whole structure of the Constitutional reform of 2018 is governed by Article 36, which adds to Article 1 of the Constitution a new paragraph, reading as follows: “The defining feature of Socialism with Chinese characteristics is the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.”

Taking this as the standpoint, the question is whether the other reforms, including the one allowing Xi to remain President for life, weakens or reinforce “the leadership of the CCP.” One persistent critic could object that the provision reinforces the Party’s current leader but not necessarily its leadership. However, Xi tells us that the stability is thus strengthened, which is good for the CCP. It sems that the general principle is, what is good for Xi is good for the Party, and what is good for the Party is good for the People.

Source: Bitter Winter