Wei Wu’s new book offers a window into a captivating, enigmatic, and mostly unfamiliar aspect of Chinese Buddhism.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, as China reeled from imperial collapse and raced toward modernity, a quiet revolution stirred in its monasteries and mountain academies. It wasn’t political, though it was deeply ideological. It wasn’t loud, though its echoes reached Tibet, Japan, and even the West. It was Esoteric Buddhism—reimagined, retranslated, and reborn.

Wei Wu’s “Esoteric Buddhism in China: Engaging Japanese and Tibetan Traditions 1912–1949 “(Columbia University Press, 2024) is not your average academic tome. It’s a portal into a world where ritual meets reform and Chinese monks and intellectuals became spiritual diplomats, negotiating the sacred across borders and centuries.

Forget the stereotype of Buddhism as serene and static. Wu’s research reveals a tradition in motion—charged with nationalism, shaped by geopolitics, and infused with tantric fire. Chinese reformers didn’t just borrow from Japan’s Shingon or Sōtō Zen schools. They turned to Tibet, embracing Vajrayāna rituals and scholastic rigor to craft a distinctly Chinese esoteric revival.

Take Nenghai (1886–1967), a charismatic monk who saw Tibetan tantra not as exotic ornamentation but as a key to restoring China’s spiritual legacy. With a scholar’s precision and a prophet’s passion, he translated texts, adapted rituals, and built bridges between traditions.

Then there’s Fazun (1902–1980), the intellectual powerhouse who translated Indian and Tibetan classics, championed Tsongkhapa’s philosophy, and argued that tantric sex rites—often scandalized by outsiders—were misunderstood and misrepresented. For Fazun, these practices weren’t immoral; they were mystical technologies reserved for the spiritual elite.

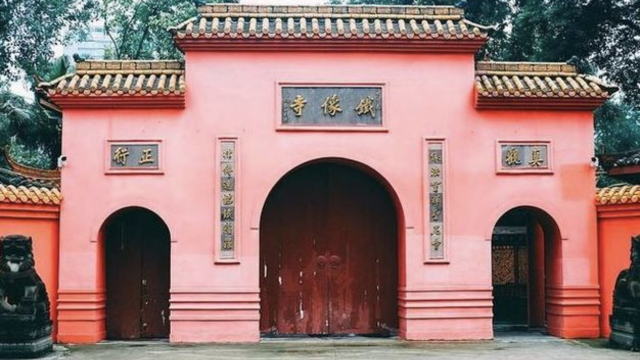

Wu’s book takes us to Mount Wutai, where the Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Institute trained monks in tantric liturgy, scripture, and discipline. But this wasn’t blind adoption—it was strategic adaptation. Chinese Buddhists weren’t passive recipients of foreign wisdom; they were curators, editors, and innovators.

And it wasn’t just monks. Lay practitioners, including women, played vital roles as translators, organizers, and even leaders. Wu’s attention to these often-overlooked figures adds texture to a narrative that’s as inclusive as it is intricate.

One of the book’s most provocative threads is how Buddhist reformers defended esoteric rituals against accusations of superstition. In an age obsessed with science and progress, they argued that tantra wasn’t irrational—it was psychologically astute, ethically grounded, and spiritually sophisticated.

Esoteric Buddhism, Wu shows, wasn’t a relic. It was a response. To colonialism. To Christianity. To modernity itself.

This isn’t just a story about monks and mantras. It’s about how traditions survive by transforming. It’s about the power of translation—not just of language, but of meaning. And it’s about how China, in the throes of reinvention, found a mirror for its complexity in the arcane symbols of tantra.

Wu’s book reminds us that the sacred is never fixed. It moves, adapts, and seduces. Sometimes, it takes the form of revolution—unless, as in China today, it is suppressed by an authoritarian regime. But that would be a topic for another book.

Source: Bitter Winter