An essential new report by the Mercator Institute reveals how the Chinese Communist Party combines Marxism and high-tech to control all features of daily life.

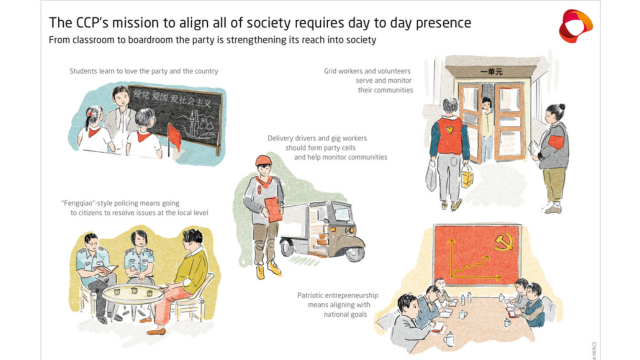

In the latest report from the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), titled “Serving the People by Controlling Them: How the Party Is Reinserting Itself into Daily Life,” authors Nis Grünberg, Katja Drinhausen, and Alexander Davey offer a chillingly lucid portrait of China’s evolving social governance model. It’s not a tale of gulags or grand purges, but of grid workers, patriotic delivery drivers, and neighborhood committees. It’s not about repression alone, but about the slow, granular reengineering of civic life—a micropolitics of presence, persuasion, and surveillance.

The report, published in August 2025, is a masterclass in institutional anatomy. It dissects the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) latest efforts to embed itself into the capillaries of society—from private firms to residential compounds, from school curricula to volunteer networks. The goal is not merely to monitor, but to mold. Not just to suppress dissent, but to preempt it by shaping the very conditions of thought and behavior.

What emerges is a vision of governance that is both intimate and expansive, a fusion of Mao-era mobilization and digital-age datafication. The Party, once content to steer from the top, now seeks to be everywhere—in your workplace, your child’s classroom, your WeChat feed, and your neighborhood dispute resolution committee. The slogan “The Party Leads Everything” is no longer rhetorical flourish. It is operational doctrine.

Xi Jinping’s third term marks a decisive breakthrough. Having centralized power and reined in big tech, the Party now turns its gaze downward. The report traces this shift to a perceived crisis of fragmentation—the social dispersion, pluralization, and hidden ruptures that emerged from decades of reform and opening. The solution? Reinsert the Party into the everyday.

Enter the Central Society Work Department (SWD), established in 2023. Its mandate is sweeping: party-building in small enterprises, volunteer coordination, and oversight of citizen petitions. It’s a bureaucratic octopus, designed to reach into spaces where the Party’s grip had loosened—the gig economy, homeowners’ associations, and youth organizations. By February 2024, every province had set up SWDs, a rollout that signals both urgency and ambition.

The SWD is not alone. The report maps a dense constellation of central organs—from the United Front Work Department to the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection—all tasked with maintaining ideological hegemony. These bodies are mirrored at every administrative level, creating a lattice of influence that spans the nation.

At the heart of this micropolitical architecture is the “grid management” system. Piloted in 2004 and expanded during the pandemic, it now covers nearly all residential areas. Each grid—a micro-zone of governance—is staffed by workers who perform a dizzying array of tasks: patrolling neighborhoods, mediating disputes, checking licenses, reporting suspicious behavior, and organizing ideological education campaigns.

The grid worker is part social worker, part informant, part Party evangelist. During COVID-19, over 4.5 million grid workers enforced quarantine rules. Today, they are the frontline of China’s surveillance state, equipped with patrol cars, cameras, and communication devices. Their salaries, modest by Western standards, represent a massive fiscal commitment: in Beijing’s Shunyi district alone, grid worker salaries totaled over CNY 172 million (more than Euro 20 million) in 2024.

Complementing grid management is the revival of the “Fengqiao experience,” a Mao-era model of grassroots governance. Its slogan—“Small issues don’t leave the village, big issues don’t leave the county”—encapsulates the ethos of local resolution. But this is no quaint return to communal harmony. Fengqiao-style policing is deeply ideological, designed to instill habitual compliance and reflexive affirmation of Party norms.

What makes the MERICS report so compelling—and unsettling—is its attention to the human infrastructure of control. Surveillance is not just technological; it is embodied. Party members, grid workers, volunteers, and patriotic entrepreneurs are mobilized as agents of alignment. They transmit norms, collect data, and enforce discipline, often without formal authority, but with implicit power.

This is governance by proximity. The Party doesn’t need to knock on your door; it’s already inside your building. It doesn’t need to censor your speech; it’s shaping your child’s textbooks. The report details how education, from kindergarten to university, is suffused with patriotic content, national security awareness, and Xi Jinping Thought. Even biology textbooks now include ideological framings.

The goal is not just obedience, but internalization. Citizens are expected to be proactive, vocal supporters of Party goals. The ideal subject is not merely compliant, but enthusiastic—a volunteer, a grid worker, a patriotic entrepreneur.

The report devotes significant attention to the Party’s penetration of the private economy. The concept of “patriotic entrepreneurship” is central. Firms are expected to align with national goals, contribute to technological self-reliance, and host Party cells. Regulations from 2021 mandate Party cells in companies with fifty or more employees, regardless of total Party membership. These cells are tasked with propagating Party policies, creating cohesion, and linking firms to local authorities.

Gig workers, too, are being recruited. Delivery drivers are encouraged to form Party cells and assist in community monitoring. This is not just about labor rights; it’s about ideological integration. The Party seeks to preempt self-organization and channel grievances into state-sanctioned mechanisms.

The MERICS report is not merely a catalogue of policies; it is a map of a new political ontology. In Xi’s China, ideology is not an accessory to governance—it is its infrastructure. The Party’s vision of modernization is inseparable from its claim to epistemic authority. Xi Jinping Thought is not just a set of slogans; it is a blueprint for social reality.

This vision is Han-centric, anti-Western, and steeped in historical destiny. The Party sees itself as the sole legitimate steward of China’s rejuvenation, and its model as superior to liberal democracy. The report notes the emergence of “whole-process democracy,” a concept that contrasts China’s system with the perceived dysfunction of the West.

Yet the report also hints at the fragility beneath the surface. Grid management is expensive. Party-building in the private sector is labor-intensive. Ideological saturation risks fatigue. The Party’s omnipresence requires constant mobilization, and the economic slowdown strains local budgets.

There is also the question of legitimacy. The Party seeks popular acceptance, not just passive compliance. But as the report notes, disillusionment is widespread, especially among urban youth and private entrepreneurs. The challenge is to maintain loyalty without resorting to overt repression. The solution, for now, is micropolitics: a thousand small levers of influence, a million points of contact.

The MERICS report concludes with a warning for international stakeholders. China’s micropolitics are not just domestic. They shape corporate governance, influence global norms, and challenge liberal assumptions. The Party’s model—resilient, adaptive, and ideologically coherent—is being positioned as an alternative for developing nations.

This is not the China of the 1990s, eager to integrate into global systems. It is a China that seeks to shape them. The micropolitics of control are part of a broader strategy of geopolitical assertion. The Party doesn’t just want to govern China; it wants to define governance itself.

“Serving the People by Controlling Them” is a sobering read. It reveals a society where care and coercion are fused, where surveillance is intimate, and where ideology is ambient. It is a portrait of a political system that has learned to be everywhere without being seen, to persuade without asking, and to govern without governing.

For readers in liberal democracies, the report is a mirror and a challenge. It asks us to consider what governance means, what legitimacy requires, and how power operates in the age of data and disillusionment.

In Xi’s China, the Party is not just in the palace. It is in the living room, the classroom, the delivery van. It is not just watching. It is shaping.

And it is doing so, as the report’s title suggests, by serving—and by controlling.

Source: Bitter Winter