A Chinese Han, who happens to physically look like a Uyghur, opens a window on the relationships between the Han majority and the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang and beyond.

By Michelle Lee

Interacting with Uyghur friends

Growing up in an autonomous region of China, a Chinese Han whom I would call JiaNan Li (he prefers his real name not to be mentioned), never thought much of having classmates who were from ethnic minorities. “I was born in the 1980s, and even then, there weren’t many of them compared to Han Chinese” he says. “But I always had the overall impression that each of the minority groups was special.”

China has consistently waved its 56 minority groups as a banner, supposedly lending truth to its projection of China as a harmonious place for all to live and prosper under the leadership of the CCP. For a while, it certainly seemed to him that this was the case. “The environment that minorities grew up in was the same as ours, but of course, we didn’t know what traditions they practiced at home,” JiaNan attests. “Minority children were even given extra points on their exams. It seemed to us their lives were in many ways preferable.”

He had Uyghur friends as a young man in his twenties traveling across China to compete in musical performance competitions, and even had a Uyghur girlfriend. In his memories of friends, the Uyghurs he knew were not particularly religious. Perhaps they ate halal, he recalled, but he never saw them practice any other aspect of Islam.

“(My girlfriend) told me if she brought a Han Chinese boy back to Xinjiang, the other Uyghurs would get really aggressive about preventing or opposing this. So, she said most girls in this situation wouldn’t go back to Xinjiang.” He also never thought much of this either and says that, while his father often remarked that the Hui Muslims in their city were “sneaky” and dishonest in their dealings with the Han Chinese, he held Uyghurs in high regard. “I always felt in my interactions with friends, particularly with friends in the music competitions, that Uyghurs had pride in their heritage, and I respected this.”

How Uyghurs became “terrorists”

“I first heard the government talk about terrorist attacks in Xinjiang in 2009. The previous summer China had just hosted the Olympics in Beijing. It was a time of great patriotic pride among Chinese. At the time, I felt hearing this news was terrifying. Of course, the news released by the Chinese government was always just to tell us that Uyghurs were dangerous. It made us all feel that we should keep distance between ourselves and them. But in the past, I had always liked my Uyghur friends. This was the first time, after hearing so much news, that I personally felt fear of them, stirred up by the Chinese government.”

Ironically, he says, he was often mistaken himself for being Uyghur. As a child, while out shopping with his mother, Chinese people would murmur, “XinJiangRen” (someone from Xinjiang) as he walked past. It was said admiringly, he recalled, as many people considered Uyghurs to be beautiful.

The dangers of looking like a Uyghur

It was only in recent years, he says, coinciding with the development of China’s so-called “reeducation programs” in 2017 that he felt reactions to his appearance, with facial features so different from many Han Chinese, was split between people who were admiring him and people who felt fear. He says that, after the uprisings in the province, they would hear news that the government was arresting Uyghur “terrorists.” “None of us thought much of this,” he says, “we just felt relief that the government was handling terrorism.” And so, no one gave much thought to the government and their response to unrest in the western regions. But now there seemed to be something different going on. Things felt different than they used to be.

He began to notice a troubling trend. Beginning in 2017, he was stopped more and more often by Chinese police, who for no apparent reason, would ask him what he was doing, where he was going, and ask to see his Chinese ID, which listed his race. “At first when I was stopped by police, I found it annoying. I had not done anything wrong, so I wasn’t nervous because they could check my ID. Sometimes if I found it too annoying, I would just say no and tell them to get lost, because I knew I hadn’t done anything wrong…why should they ask me? Was it only because I looked Uyghur? Sometimes they would give up because I spoke locally accented Mandarin…If I had really been Uyghur? What would have happened to me then? If they even heard a Xinjiang accent in another city, they would certainly detain me.”

One day, his view of these incidents as annoying transformed into suspicions of something darker, when he was stopped in the airport while traveling with his wife, and informed that he needed to show his passport because “people from Xinjiang can’t hold a passport.” His wife was furious, and let loose a string of angry questions. After checking his Chinese ID, the officer apologized for the inconvenience and walked off. “My wife knew before I did…after that she began to ask people about this policy and investigate more. As a foreigner, she had access to a VPN.” JiaNan is quick to acknowledge that even with his wife, who is a foreign citizen, sharing knowledge and facts with him, he was still not immediately inclined to criticize the Chinese government.

The persecution of Uyghurs: truth and propaganda

When I asked if he thought the average Han Chinese citizen, if confronted with the truth of the atrocities committed against Uyghurs, would act to support or defend them, he answered, “It depends on the situation. If they knew the situation in its entirety, then perhaps yes. For people like myself, race does not matter. But, then again, I am a Christian and I now know the true colors of the CCP, because we are often persecuted for our faith as well. But if you had asked me a few years ago, I had a different opinion. I used to argue with foreign friends about the government all the time. I got really offended. I was offended because I felt foreigners always talked about the Chinese government and all those topics that make a Chinese person automatically defensive, because we are brainwashed from the time we are young to never question the government.”

He identifies this as the most important problem to understand about China and the average citizen’s thought process. “Even my family, my mom, my sister, my best friends…. they are unable to believe these things (about Uyghurs suffering genocide). The long-term indoctrination of Chinese people, starting from the time they are children is really scary and evil. It makes people unable to form their own thoughts and opinions. The ability to solve problems through individual thought is nonexistent in most people.”

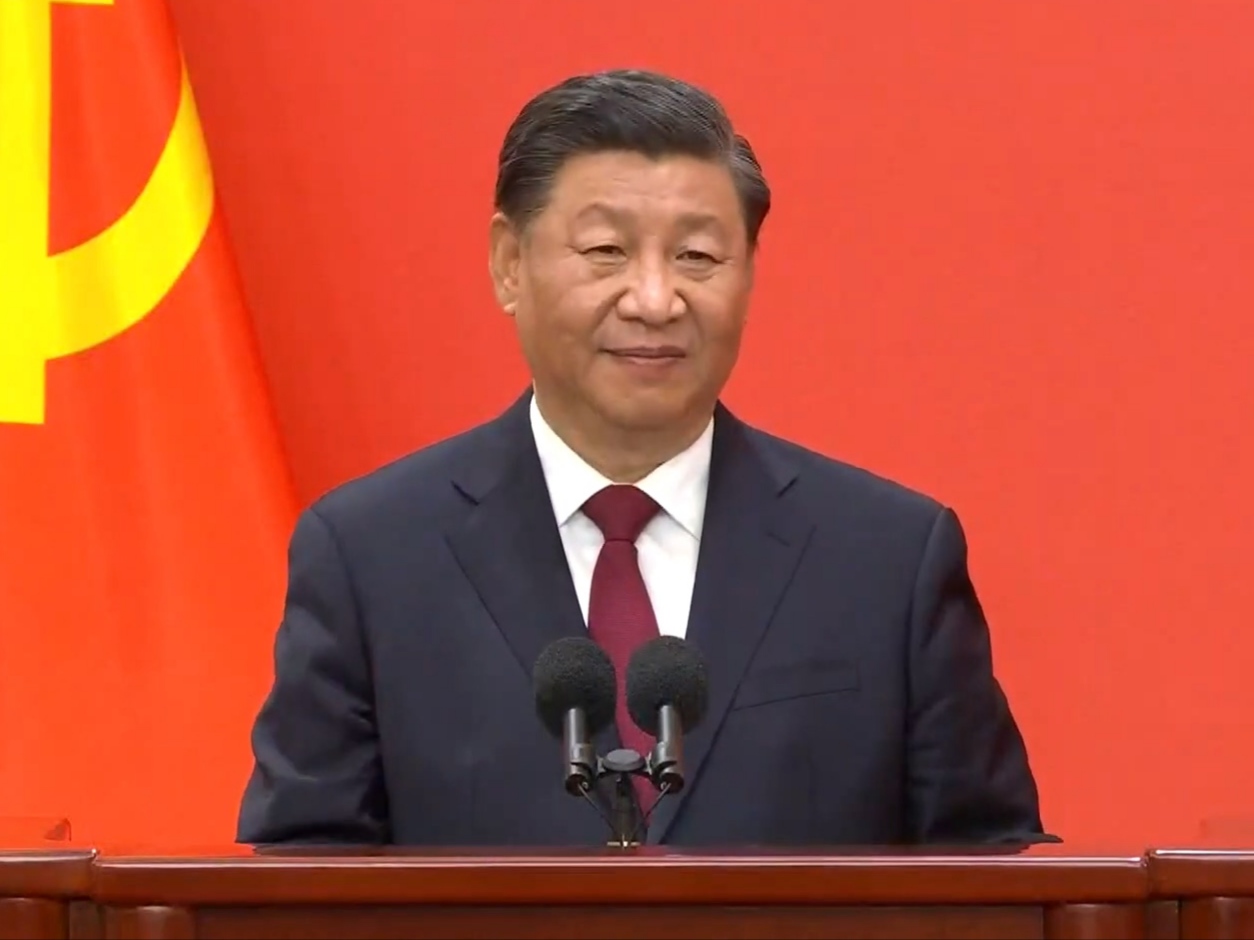

In hearing these comments, his sadness can be felt. He expresses the alienation he has felt since becoming a more vocal critic of the CCP, and he says that the recent pandemic unleashed by China’s policies of oppression and suppression of truth have completely turned him from timidity to tenacity. He is now a vocal advocate for those suffering as a result of the CCP’s reign of tyranny under Xi Jinping.

“Whatever I say to friends now, they don’t believe,” he explains. “Even statements they feed unanimously back to me, like ‘China is much safer than the West’ show their ignorance of truth. Even with this virus, Chinese people still cannot believe the government would do anything bad.”

“The virus changed everything”

I ask JiaNan how his thinking evolved from being relatively neutral to the government to believing that the CCP is the greatest evil the world faces today. “Because of the coronavirus. I used to be on a different page even from my wife about many things, but after this virus, I truly began to investigate everything for myself, including things we had argued about before. A government who will lie to their own people about a deadly pandemic will lie about everything… I discovered the truth about so many things they had lied about, even the reputation of the Uyghurs was deliberately construed to be a certain way for their own agenda.”

When asked what he considers the best hope for Chinese people to know and uphold truth, “To destroy the CCP,” he answers without missing a beat. He watched a documentary recently, he said, that included the quote by photographer Peng Wang: “This indoctrination destroys a person’s humanity, individuality, and conscience.” “I completely agree with this quote.” JiaNan says. “Because of this indoctrination of teaching people to fear, no one would stand up in this way to the CCP, unless something horrible happened to them personally.” He concludes that, “As a Uyghur in China, it must be impossible to live.”

Source: Bitter Winter